- 8 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 9 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 10 Dec 20#thewayahead (under scrutiny)

- 11 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 12 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 13 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 15 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 16 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 17 Dec 20#thewayahead #hookland

- 18 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 19 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 20 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 21 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 22 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 23 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 24 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 25 Dec 20#thewayahead In our family we call this the Britain tree from its vague Albion form. Sadly Kent snapped off a few months ago in a storm. Prescient? But if you look closely you can see #Hookland. Merry Yule, all.

- 26 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 27 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 28 Dec 20#thewayahead #winterbourne (Confession: I abandoned this way ahead and walked two extra miles to avoid it…)

- 29 Dec 20#thewayahead

- 30 Dec 20#thewayahead Today’s choice was between arty shots of icy puddles, or this, which has mysteriously sprouted in the last few days. Obvious winner.

- 31 Dec 20#thewayahead It’s said the poet Thomas Bridewell loped through these woods to #Hookland in a fugue state. His journal entries are fragmentary, elusive, but I can see which way he went.

- 1 Jan 21#thewayahead An old soldier, standing steadfast while humans come and go down the ages.

- 2 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 3 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 4 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 5 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 6 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 7 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 8 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 9 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 10 Jan 21A lost sole on #thewayahead

- 11 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 12 Jan 21Keeping watch over #thewayahead

- 13 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 14 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 15 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 16 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 17 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 18 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 19 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 20 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 21 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 22 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 23 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 24 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 24 Jan 21@SlowWaysUK @nsummers1234 Oxfordshire Cotswolds (see #thewayahead)

- 25 Jan 21#thewayahead #snowways

- 27 Jan 21“In my laudanum-tinctured fever it seemed as if the very trees reached out to grasp me.” – Thomas Bridewell, Journal #thewayahead #hookland

- 28 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 30 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 31 Jan 21#thewayahead

- 1 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 2 Feb 21#thewayahead – snowdrops for #Candlemas and #Imbolc

- 3 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 4 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 5 Feb 21Well quite. #thewayahead

- 6 Feb 21Lost and bewildered at the Round Castle earthwork, Thomas Bridewell wrote in his journal of the moss men, but this has always been attributed to his condition. #thewayahead @HooklandGuide

- 6 Feb 21Some of us bite. #thewayahead

- 7 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 8 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 9 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 10 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 11 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 12 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 13 Feb 21#thewayahead Icy path snaking forth, as though we’re in the wake of Andy Goldsworthy.

- 14 Feb 21#thewayahead – oh, and #thewayback and #thewayover, etc

- 15 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 16 Feb 21#thewayahead (a Covid ‘priority postbox’ serving four rural houses and which is too small for the test boxes anyway!)

- 17 Feb 21Signs of hope on #thewayahead

- 18 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 19 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 20 Feb 21#thewayahead Last of the hipsters?

- 21 Feb 21#thewayahead #theneighahead

- 22 Feb 21#thewayahead #cryptozoology

- 23 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 24 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 25 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 26 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 27 Feb 21#thewayahead 6-mile maiden voyage for new boots. Happy face.

- 28 Feb 21#thewayahead

- 1 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 2 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 3 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 4 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 5 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 6 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 7 Mar 21#thewayahead Squint and you could be on Easter Island…

- 8 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 9 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 10 Mar 21So today is my 100th #thewayahead picture in a row (and the first time I’ve cheated by not using a picture taken on the same day). I’m going to stop this now, and just post more interesting shots occasionally. 1/3

- 13 Mar 21#thewayahead … but which one?

- 18 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 25 Mar 21After 10 years here there’s only one footpath within 3 miles that I’ve never been on (largely because it involves a busy B road at one end). Achievement unlocked. #thewayahead

- 28 Mar 21#thewayahead

- 6 Apr 21#thewayahead

- 11 Apr 21#thewayahead

- 12 Apr 21#thewayahead on 12th April?!

- 15 Apr 21“An ancient, hungry king beneath the tump, his maw enarboured” – Thomas Bridewell, ‘Anthropophage’, 1874. #FolkloreThursday #thewayahead #hookland

- 16 Apr 21#thewayahead

- 23 Apr 21#thewayahead – today marks my 400th consecutive daily walk (min. 3 miles, max. 25 miles, ave. 5.8 miles)

- 27 Apr 21Somebody may be hopping on #thewayahead

- 30 Apr 21Now *this* is someone who knows about #thewayahead – Why I’m running 5,000 miles around the coast of Britain solo theguardian.com/travel/2021/ap…

- 2 May 21#thewayahead

- 15 May 21#thewayahead

- 25 May 21#thewayahead

- 29 Jun 21We’re hitting Peak Green on #thewayahead

- 13 Jul 21#thewayahead #slowways

- 24 Jul 21#thewayahead

- 1 Aug 21I was walking regularly anyway but lockdowns etc focused me on consistency. Today is Day 500. (Rule is bare minimum of 3 miles but average is about 5.5.) Now what? #thewayahead

- 2 Aug 21#thewayahead

- 9 Aug 21#thewayahead

- 13 Aug 21#thewayahead

- 13 Aug 21This amazing place is one of the two quarries in Wales where the bluestones of #Stonehenge came from. #thewayahead

- 19 Aug 21#thewayahead

- 20 Aug 21#thewayahead

- 31 Aug 21#thewayahead #thewaybehind

- 11 Sep 21#thewayahead

- 15 Nov 21#thewayahead

- 16 Nov 21#thewayahead ?

- 20 Nov 21#thewayahead

- 21 Nov 21Might not be on #thewayahead much longer – both kids have Covid…

- 26 Nov 21#thewayahead Have just walked a mile up and down this corridor (self-isolating), accompanied by @jonronson’s excellent Things Fell Apart

- 2 Dec 21Out of isolation, battered but active, and back on #thewayahead

- 18 Jan 22#thewayahead

- 28 Jan 22One of today’s signs on #thewayahead – one for @nickhayesillus1 and @guyshrubsole – whatever a ‘sunbath’ is.

- 22 Feb 22Glad my old friend is still here on #thewayahead

- 29 Mar 22Moss on #thewayahead

- 2 Apr 22Ah, the colours of spring on #thewayahead

- 3 Apr 22The what?! #thewayahead

- 10 Apr 22#thewayahead

- 11 Apr 22#thewayahead

- 13 Apr 22Bathtime on #thewayahead

- 14 Apr 22Giving #thewayahead some welly.

- 15 Apr 22Early Netflix? #thewayahead

- 19 Apr 22Gulp. #thewayahead

- 6 May 22Folk horror on #thewayahead? Or perhaps a slip into #hookland.

- 27 May 22Choices for #fingerpostfriday @FingerpostFri on #thewayahead

- 30 May 22#thewayahead

- 7 Jun 22Bee. Cranesbill. #thewayahead

- 7 Jun 22Papaverousness on #thewayahead

- 13 Jun 22Oh yes. #thewayahead

- 5 Jul 22Small skipper and scabious on #thewayahead

- 10 Aug 22Glowing tunnel on #thewayahead

- 10 Aug 22Night walk, railway, harvest moon. #thewayahead

- 12 Aug 22Choices on #thewayahead for #FingerpostFriday

- 26 Aug 22Enough ways for you on #thewayahead? #fingerpostfriday

- 29 Aug 22#thewayahead

- 30 Aug 22Gulp. #thewayahead

- 2 Sep 22I’m not sure this is strictly canonical for #fingerpostfriday but it unambiguously shows #thewayahead…

- 16 Sep 22A sunny face on #thewayahead

- 7 Oct 22Happy #fingerpostfriday 🥾 #thewayahead

- 14 Nov 22An atmospheric start to #thewayahead today.

- 17 Nov 22Gotta love autumn on #thewayahead

- 8 Dec 22The tree’s embrace on #thewayahead

- 15 Dec 22A cheeky -8.6° on #thewayahead today.

- 1 Jan 23The zigzag of 2023 on #thewayahead

- 27 Feb 23A guiding hand on #thewayahead

Category: places

A collection of #fingerpostfridays

- 6 May 22One from a couple of weeks ago for #fingerpostfriday

- 6 May 22OK, permit me a repost now that I know about @FingerpostFri #fingerpostfriday – but this time without the feeble Netflix gag.

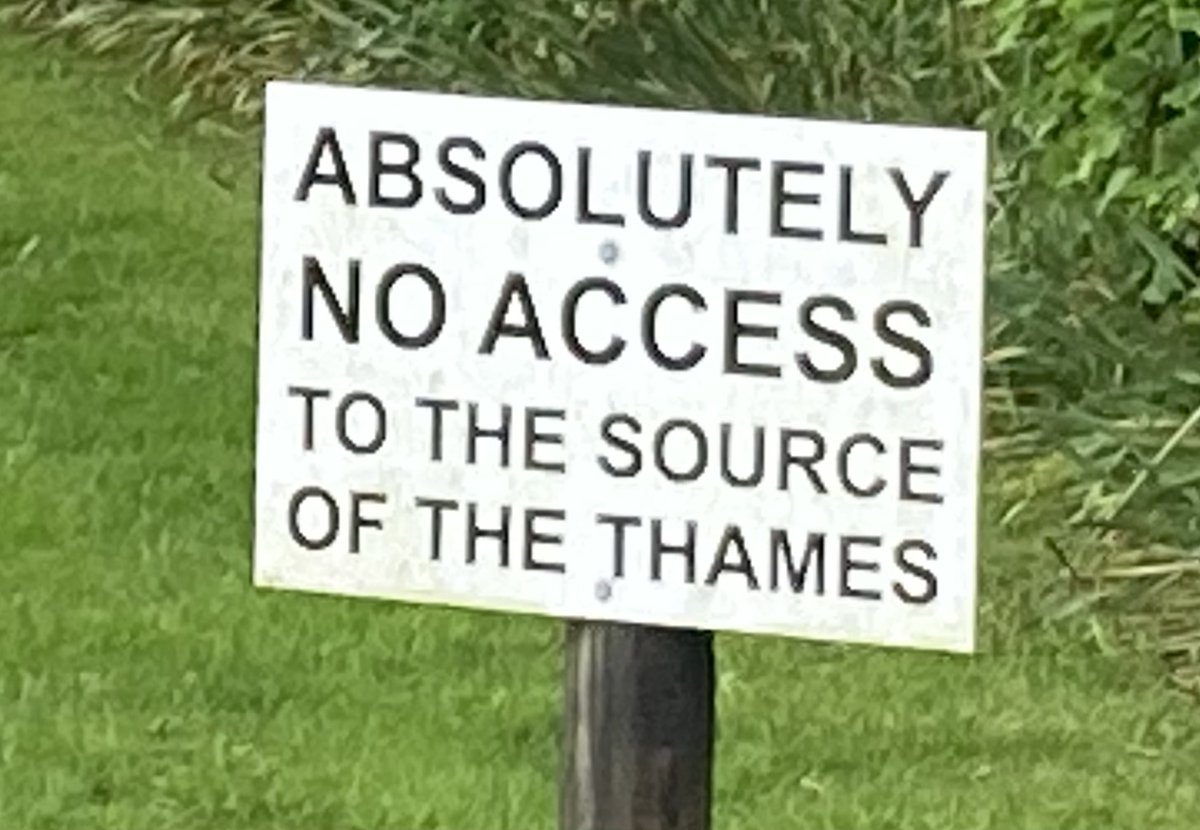

- 20 May 221. So my new thing here is the #10tweetadventure – exploring corners of history or landscape, but told in no more than 10 tweets. Today, for @FingerpostFri #FingerpostFriday, let’s start with the source of the River Thames. Except… it isn’t.

- 27 May 22Choices for #fingerpostfriday @FingerpostFri on #thewayahead

- 17 Jun 22Something from this week for #fingerpostfriday

- 5 Aug 22And speaking of #FingerpostFriday …

- 12 Aug 22Choices on #thewayahead for #FingerpostFriday

- 26 Aug 22Enough ways for you on #thewayahead? #fingerpostfriday

- 2 Sep 22I’m not sure this is strictly canonical for #fingerpostfriday but it unambiguously shows #thewayahead…

- 2 Sep 22Here’s a more canonical #fingerpostfriday entry from this week’s walking.

- 9 Sep 22Take your pick for #fingerpostfriday

- 16 Sep 22Something for #fingerpostfriday – and my latest newsletter is about the place where you can find them… gethistories.com/p/most-secret-…

- 23 Sep 22For #fingerpostfriday, this is always a welcome sight on a walk I do most weeks.

- 7 Oct 22Happy #fingerpostfriday 🥾 #thewayahead

- 28 Oct 22Another week, another county, another walk, another #fingerpostfriday

- 25 Nov 22Back with an old friend for #fingerpostfriday

- 9 Dec 22Is it too late for #fingerpostfriday?

- 16 Dec 22Wait, what? A round trip for #fingerpostfriday @FingerpostFri

- 30 Dec 22A bit wadey this #FingerpostFriday

- 6 Jan 23Land vs water. #fingerpostfriday

- 20 Jan 23Twas a crisp morning walk for #fingerpostfriday today.

- 27 Jan 23Happy birthday to @FingerpostFri #fingerpostfriday

- 10 Feb 23RT @richardf: So, for #FingerpostFriday, here’s (I think) Britain’s first European walking route sign. Installed yesterday in Charlbury. Tu…

- 24 Feb 23Something for everyone on #fingerpostfriday

- 10 Mar 23Am I allowed the oldest kind of waymarker for #fingerpostfriday?

- 24 Mar 23Decisions, decisions for #fingerpostfriday

- 28 Apr 23It’s #fingerpostfriday – you can go that way, or that way. Or somewhere else.

- 5 May 23It’s #fingerpostfriday – unless you’re a horse.

- 12 May 23There are always choices on #fingerpostfriday

- 19 May 23And here’s the confluence of #fingerpostfriday and #dunstanday twitter.com/chapmanbookman…

- 26 May 23This way? #fingerpostfriday

- 9 Jun 23HOW MUCH?! #fingerpostfriday

- 16 Jun 23A disconcerting #fingerpostfriday

- 30 Jun 23A slightly more serious note for #fingerpostfriday this week. This wonderful path runs through a local ancient woodland. (1/4)

- 4 Aug 23Where now? Who cares, it’s beautiful. #fingerpostfriday

- 25 Aug 23Keep thinking of leaving Twitter but then #fingerpostfriday brings me back…

In the footsteps of Celia Fiennes in York

So in 1697, Celia Fiennes arrived solo in York on horseback as part of her unique tour of England. I followed in her footsteps around York Minster today. Join us! Words by Celia, pictures by me. #yorkminster #10tweetadventure

In search of St Dunstan: a London walk

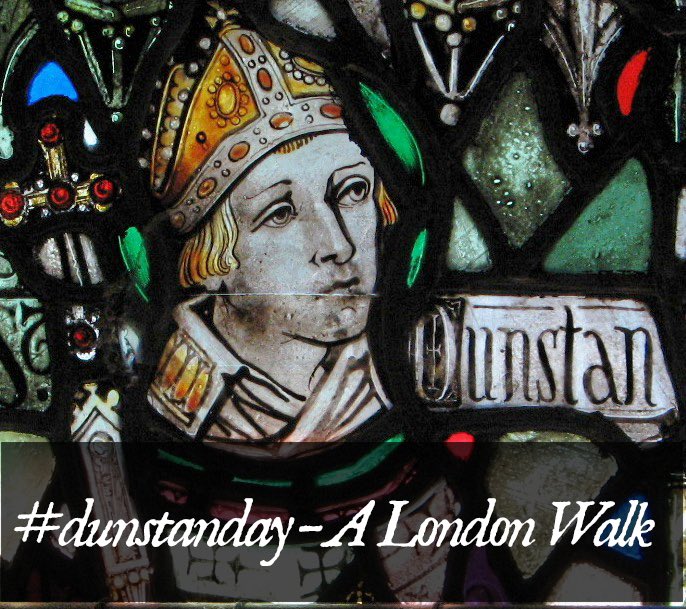

Amazingly it’s over a year since my last #10tweetadventure celebrating #pancrasday. So what better than tracking down another saint, this time more intimately associated with London. On St Dunstan’s Day, 19 May, I give you… #dunstanday

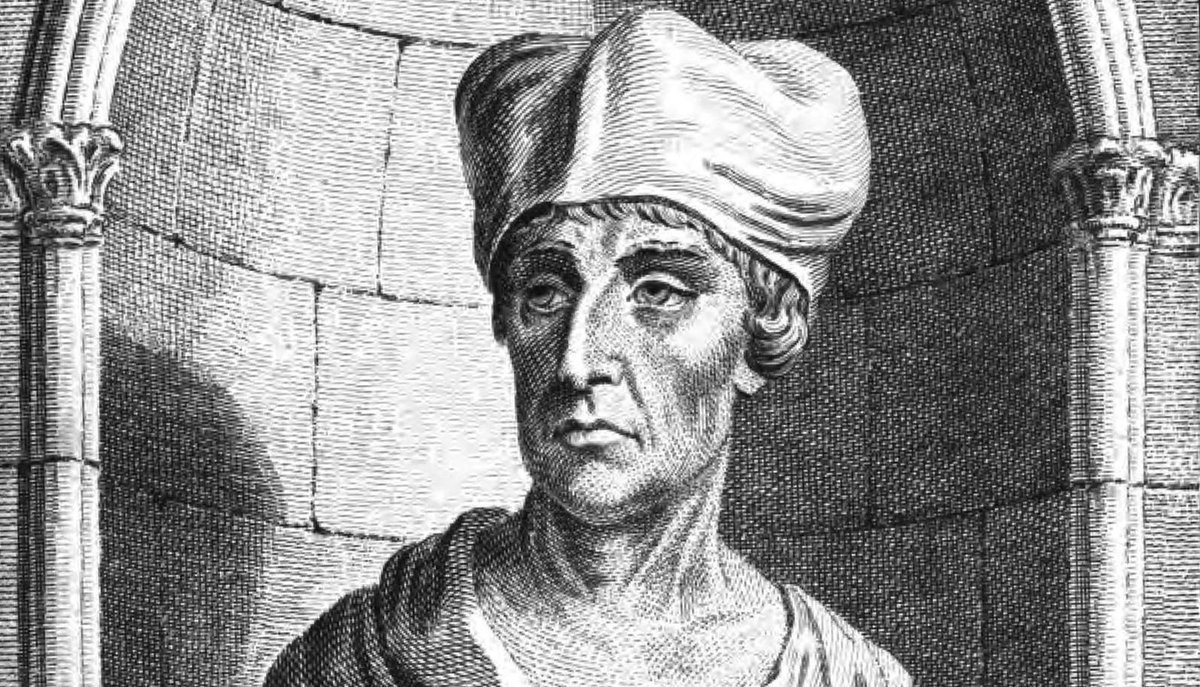

1 Dunstan (c.909-988) was a proper English (Saxon) saint. He was born in Baltonsborough, Somerset, near Glastonbury where he became abbot. He was later bishop of Worcester, then of London, and Archbishop of Canterbury (serving 7 kings!). Here’s his alleged selfie. #dunstanday

2 It’s thanks to Dunstan we have lucky horseshoes (the story goes he nailed one to the Devil’s hoof, as well as tricking Old Nick in other ways – see picture). A craftsman and scholar himself, he’s the patron of metalworkers, jewellers and locksmiths. #dunstanday

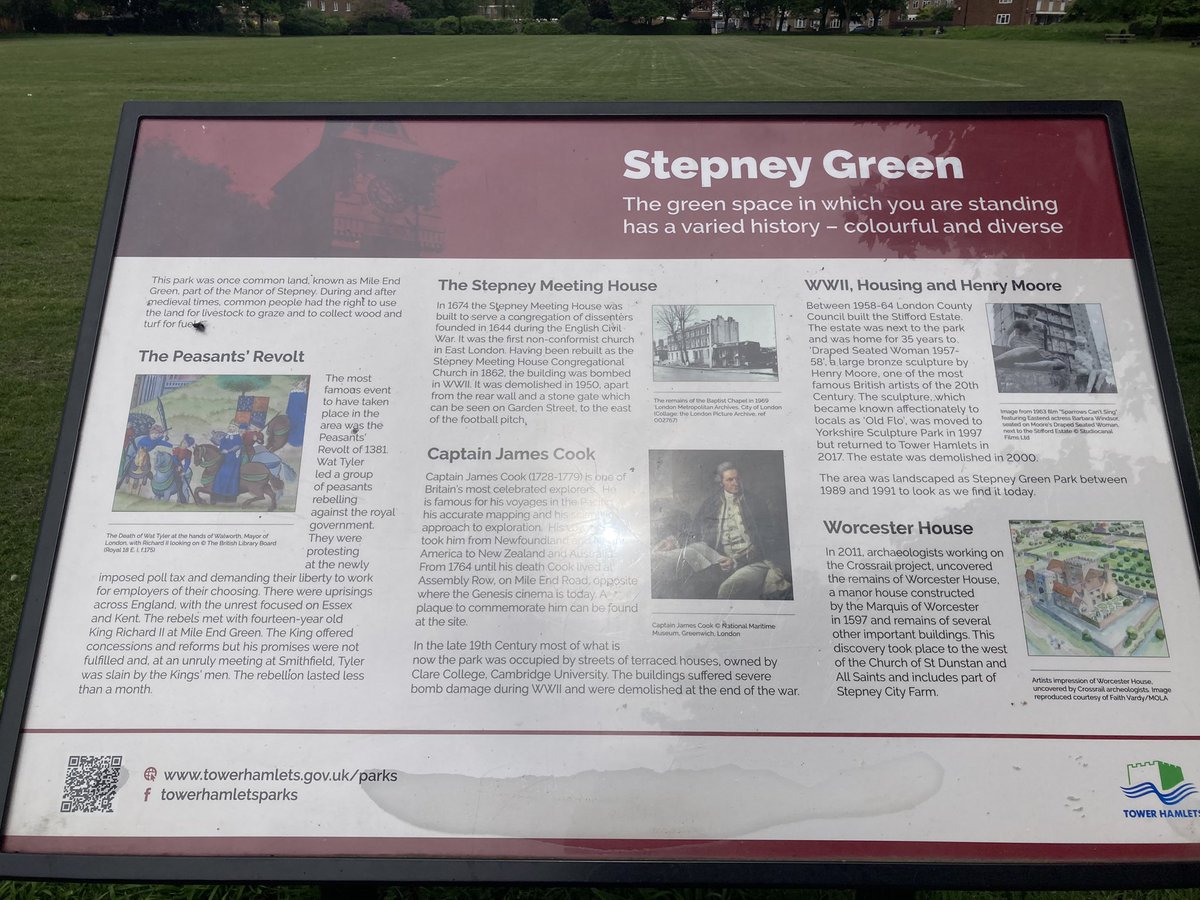

3 We start in Stepney at St Dunstan & All Saints (Church of the High Seas) rebuilt by Dunstan himself (who may have lived nearby), and again in the 15th & 19th C. A Saxon rood cross survives. 17th C herbalist & hermit Roger Crab is buried here (see below). #dunstanday

4 This is all that remains of Whitechapel Bell Foundry (which provided bells at St D’s in Stepney). A sad end for a business that started in the 16th century (but @savetheWbf offers hope). St D allegedly cast bells himself and became the patron of bellringers. #dunstanday

5 The City: all that remains of St Dunstan-in-the-East is this haunting garden. It dates from c.1000, expanded 1391 and patched up in the 1660s after the Great Fire, with a new Wren spire. It was rebuilt again in the 1810s before the 1941 Blitz finally did for it. #dunstanday

6 A detour to Guildhall Art Gallery (@GuildhallArt) & its treasures, including a Roman amphitheatre only found in 1988. (Alas we were unable to look inside the Great Hall, where the figures of Gog & Magog can be found – but we’ll meet them again later anyway…) #dunstanday

7 Westward, to our 3rd church… St Dunstan-in-the-West. It dates from Norman times, rebuilt in the 1830s. Bible translator William Tyndale preached here and poet John Donne was rector. Walton’s Compleat Angler was published here. Predatory Pepys plagued maids here. #dunstanday

8 St D-in-the-W ‘s treasures include this 1586 statue of Elizabeth I moved from the lost Ludgate; a crumbling statue of King Lud himself, with his two sons; up in the tower, the bells are struck hourly by these figures of giants Gog and Magog (or Gogmagog & Corineus) #dunstanday

9 Oddly all 3 churches had 17th C wood carvings by Grinling Gibbons; only one survives – the communion rail here. (Apologies to St Dunstan’s in Cranford Park (too far!) – where Tony Hancock’s ashes lie – & l all the many St Dunstan churches across southern England.) #dunstanday

10 If you’ve enjoyed #dunstanday, see #Pancras day, #10tweetadventure and #londonfogg, or subscribe to my history newsletter (@gethistories, link in bio). The latest edition tells the story of Roger Crab!

Follow-up, 20/6/23

Some offcuts/extras from yesterday’s #dunstanday walk 1/3. Memorial in Stepney; history of Stepney Green; The Good Samaritan pub; Royal London Hospital’s crumbling former outpatients building.

#dunstanday offcuts 2/3. A Cornhill alley; an historic well; the philanderer Pepys; Queen Vic’s diamond jubilee.

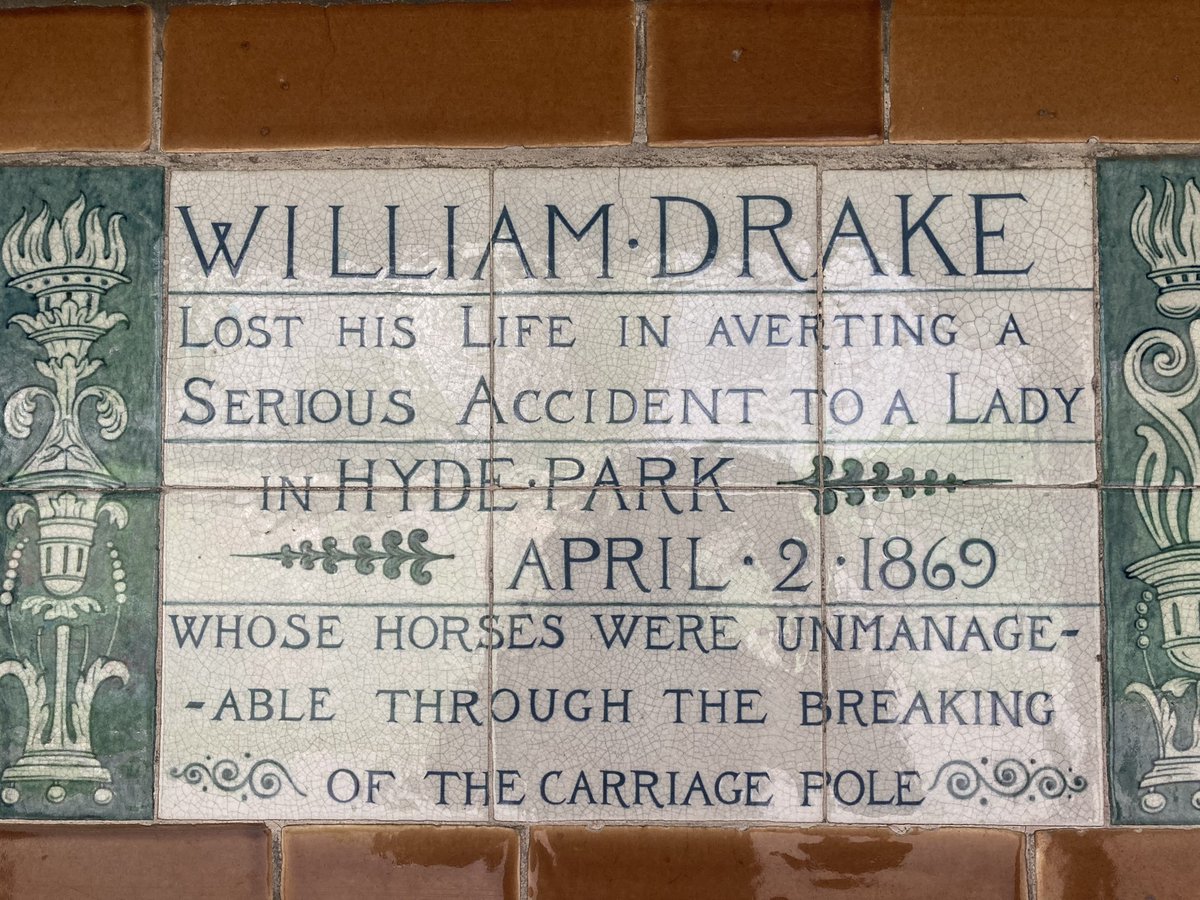

And #dunstanday offcuts 3/3. Postman’s Park; the garden at Wren’s Christ Church Greyfriars; Confucius at Clifford’s Inn (in fact the old churchyard of St Dunstans-in-the-West where publishers sold books 👋@joe_saunders1); and The Old Bank of England pub.

The wild men of Buckinghamshire (a walk)

It’s time for a quick write-up of yesterday’s walk: a new #10tweetadventure. This one isn’t probing any particular mystery in depth, but I can at least offer you a wild boy, a wild man and several green men. So no need for a stony expression. 1/10

We begin in Northchurch, in a corner of Hertfordshire poking towards Buckinghamshire – and here is the simple grave of an 18th century phenomenon: Peter the Wild Boy. He was found living feral in the woods near Hamelin by George I out on a hunting holiday. 2/10

Peter was brought back to live among the king’s courtiers. Here he is – clutching some acorns in a painting by William Kent on the staircase of Kensington Palace, and shown in later life: he lived until his 70s, albeit without learning to speak more than a few words. 3/10

Our walk took us to the Ridgeway – and here’s a little chunk of the mysterious Grim’s Ditch, an earthwork that may be a boundary, or not, dating to the Iron Age, or not – perhaps related, or not, to the bits of Grim’s Ditch near where I live in Oxfordshire. 4/10

At the far end of the Ridgeway – here, also the ancient Icknield Way – is Ivinghoe Beacon, an Iron Age hillfort (and a film location for 4 Harry Potters and The Rise of Skywalker, The Avengers (Steed not Marvel) & more). 5/10

A steep chalky plunge into the vale leads to the village of Ivinghoe. History has also spelt it Evinghehou, Iuingeho, Hythingho, Yvyngho… and Walter Scott called it Ivanhoe, extrapolating a short old rhyme into a 180,000 word novel. 6/10

Ivinghoe’s church has a fantastic collection of green men and other odd Tudor-era figures, including a mermaid (which I forgot to photograph) and some bat-like angels (which I didn’t). 7/10

Over the fields and past Pitstone Mill – this is the ‘earliest dated’ windmill in Britain, from 1627 but quite possibly older. The National Trust gent there invited us to enter and “touch something 1000 years old”. I said I could always shake his hand instead. Oops. 8/10

And Pitstone’s church, now redundant, has what’s claimed to be another green man, in a 15th century piscina (ecclesiastical washbasin). But the best thing of all on the walk has to be… 9/10

This incredible wild man or wodewose, holding his ragged staff, in Aldbury church. Cheeky Sir Robert Whittingham (c.1429-71) is resting his plates on this amazing figure, which brings us back in a way to the wild boy we started with. 10/10

(PS Oops, I forgot the Whipsnade White Lion! England’s largest chalk figure, no less, made in 1933 – to scare away planes from scaring the zoo animals – and restored in 2018. 11/10)

Where is the real source of the River Thames?

1. A #10tweetadventure – exploring corners of history or landscape, but told in no more than 10 tweets. Today, let’s start with the source of the River Thames. Except… it isn’t.

2. For one thing, the site in Trewsbury Meadow has totally dried up – fair enough, it was always seasonal. But half a mile downstream is Lyd Well, in the area marked on old maps as Thames Head. But alas this was bone dry today too.

3. The fons et origo, as it were, of historical accounts that this Thames Head is the source go back to John Leland in 1542: “Isis riseth at three myles from Cirencestre, not far from a village cawlled Kemble, within half a mile of the Fosseway, wher the very head of Isis is”.

4. But hang on: in 1598 John Stow wrote “this famous streame hath her head… about a mile from Tetbury, neare unto the Fosse, (an highway so called of old)”. But Thames Head is 6 miles from Tetbury, even as the crow flies. I’ve found a nearer candidate, only 2 miles from Tetbury!

5. This is near the ultimate source of the Swill Brook (also dry alas). Its very brief Wikipedia page quips about it being bigger than the Thames where they meet. Er, hang on! Bigger? Also pictured here are where they meet, the weedy Thames thereafter and the lily-padded Swill.

6. But as well as bigger, it’s longer! From Lechlade to Thames Head is 33.7km (I’ve measured it using specialist OS data). From Lechlade to the Swill’s source is… 39.5km! So apologies to Old Father Thames in Ashton Keynes here, but you’re in the wrong place, mate. But wait…

7. There’s even a further possibility mentioned in @PaulWhitewick‘s excellent recent thread and video about some of this, referring to a leak from the Thames and Severn Canal, further up than Thames Head.

8. As Paul mentions, it’s an open secret that the *real* source is Seven Springs, known as the mouth of the tributary River Churn. Here it is, bubbling happily, a whopping 52.7km from Lechlade & making the Thames waters longer than the Severn. But… there’s a further source yet!

9. A bit W of there is this pond at Ullenwood’s college & a nearby stream – bubbling happily, a whole 54.8km from Lechlade, and feeding into the ‘Churn’. Thames Head is so utterly geographically – and even historically – wrong! Ah well: it won the gong, so the ‘source’ it is.

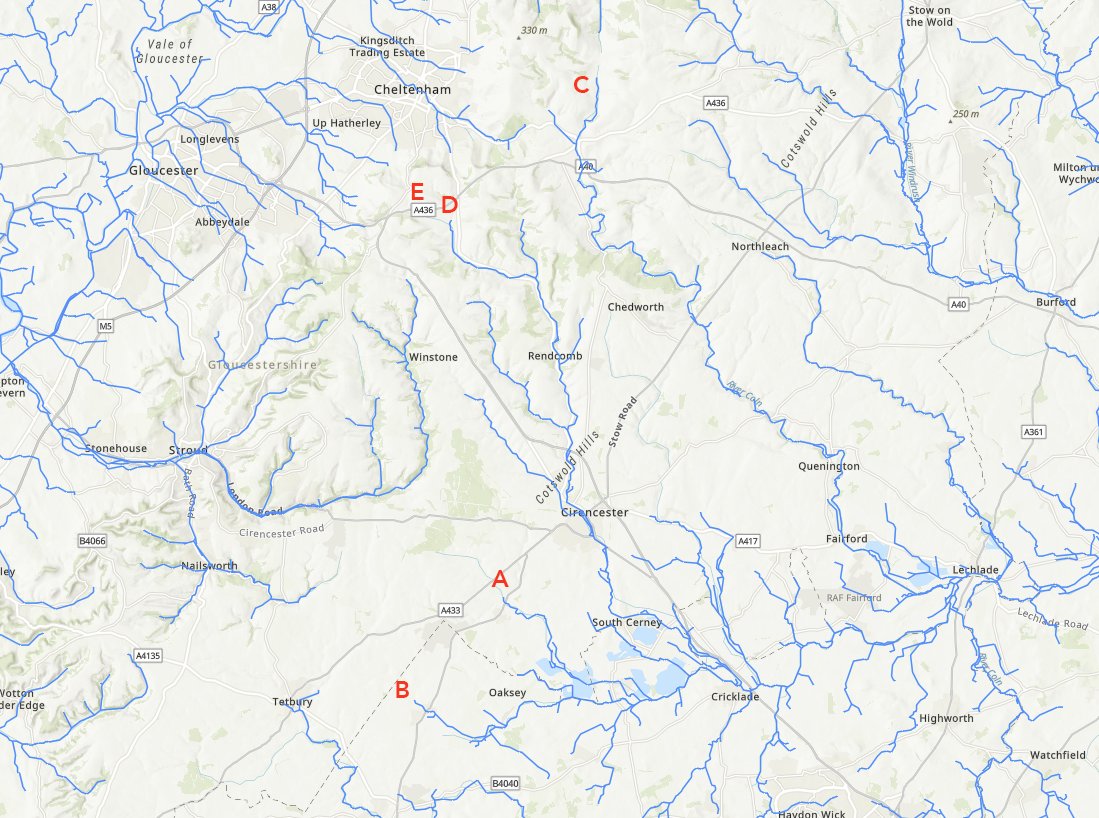

10. Even the source of the tributary Coln is 49.km from Lechlade. Thames Head isn’t even technically in the top 10 distance-wise! This map (OS Open Rivers data) shows A: Thames Head B: Swill Brook C: River Coln D: Churn (Seven Springs) E: Churn (Ullenwood). Bye!

In search of St Pancras: a London walk

Today I’m embarking on another London walking expedition… Join me on a 6-mile walk as I listen to the echoes of a Saxon-era cult, and learn about some literary legends, lost spas… and a walrus. I give you: #pancrasday

Today, 12 May, is the feast of Saint Pancras, a little-known saint whose name is writ large in London, and commemorated in various UK churches. He was a 3rd century Turkish-born Roman who converted to Christianity & was beheaded c.304AD, perhaps by emperor Diocletian. #pancrasday

Pancras/Pancratius (whose name means holder-of-everything) was venerated by the 5th century (he’s patron of children). Allegedly his head remains to this day in Rome’s basilica of San Pancrazio. But how come he’s all over (mostly southern) Britain? #pancrasday

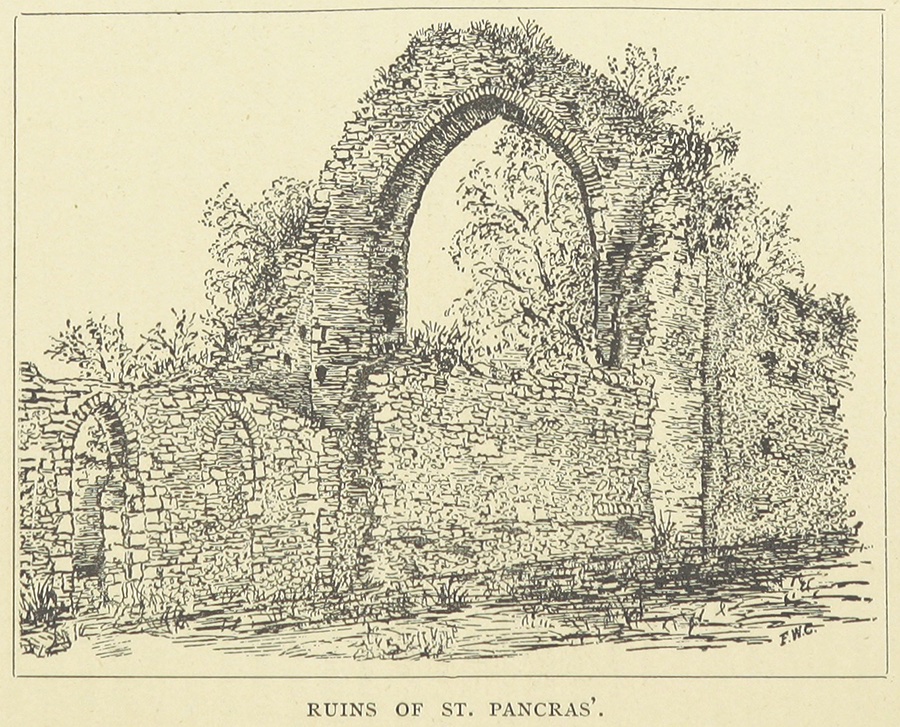

The answer lies with St Augustine, the chap who came to Canterbury in 597AD & brought relics of Pancras with him (history does not record which bits) & the associated cult. Augustine’s 1st church in Canterbury (see pic of surviving ruins) was dedicated to Pancras #pancrasday

Plus a story tells that the monastery in Rome where Augustine had been prior was built on land once owned by Pancras’s family. Bede wrote of the relics in Northumbria c.60 years after Augustine came – Pancras became important here. Join me at 11am! #pancrasday

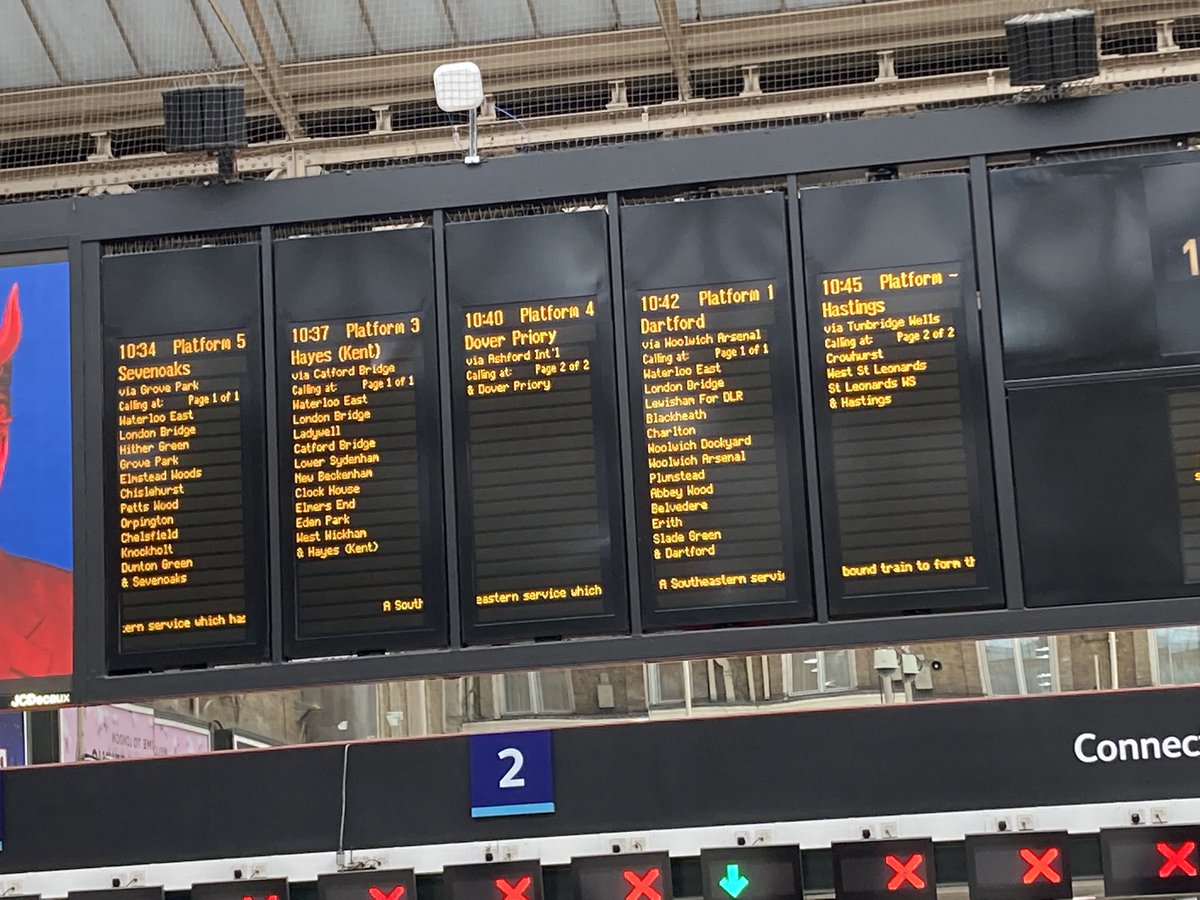

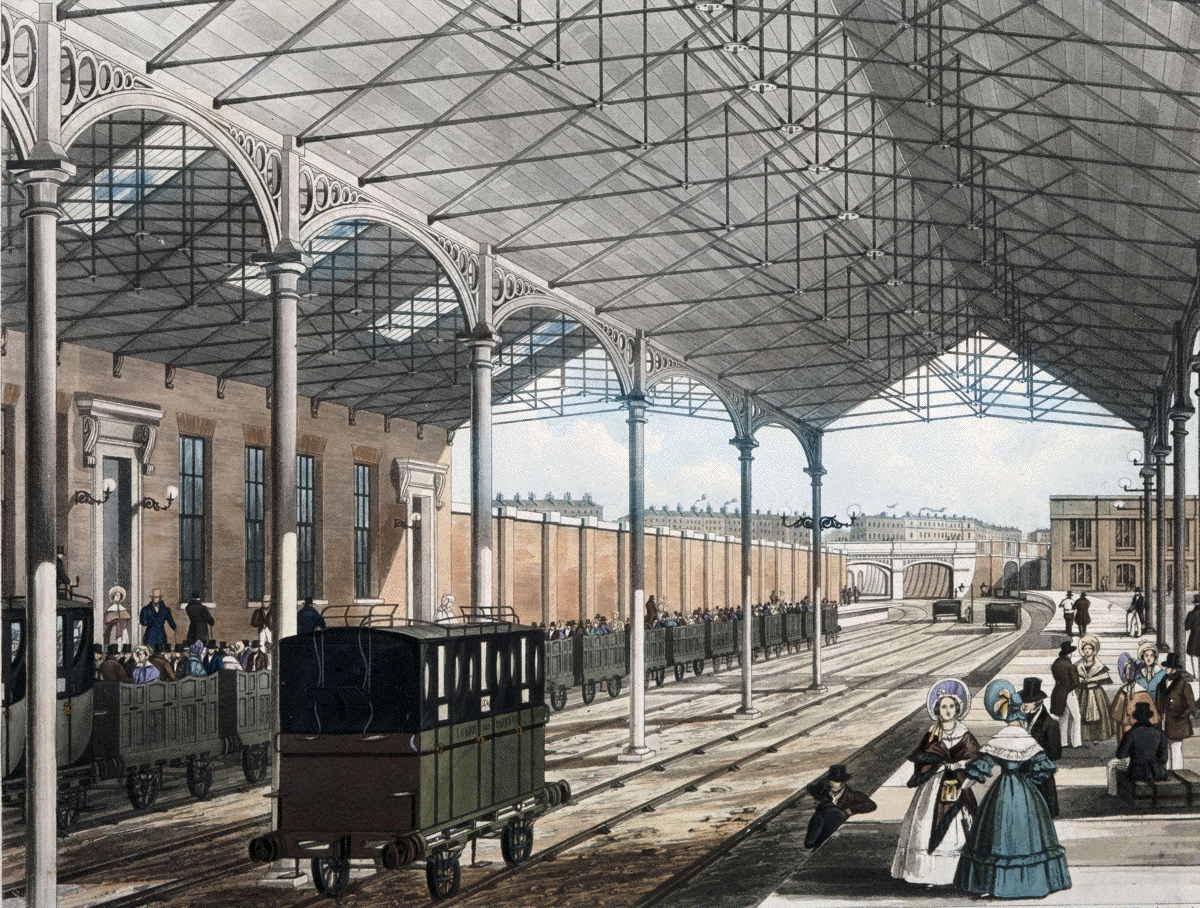

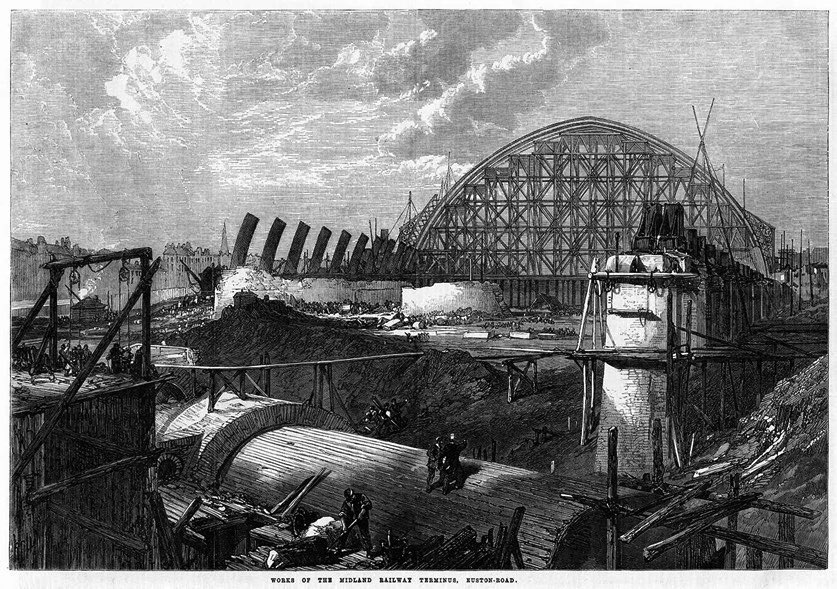

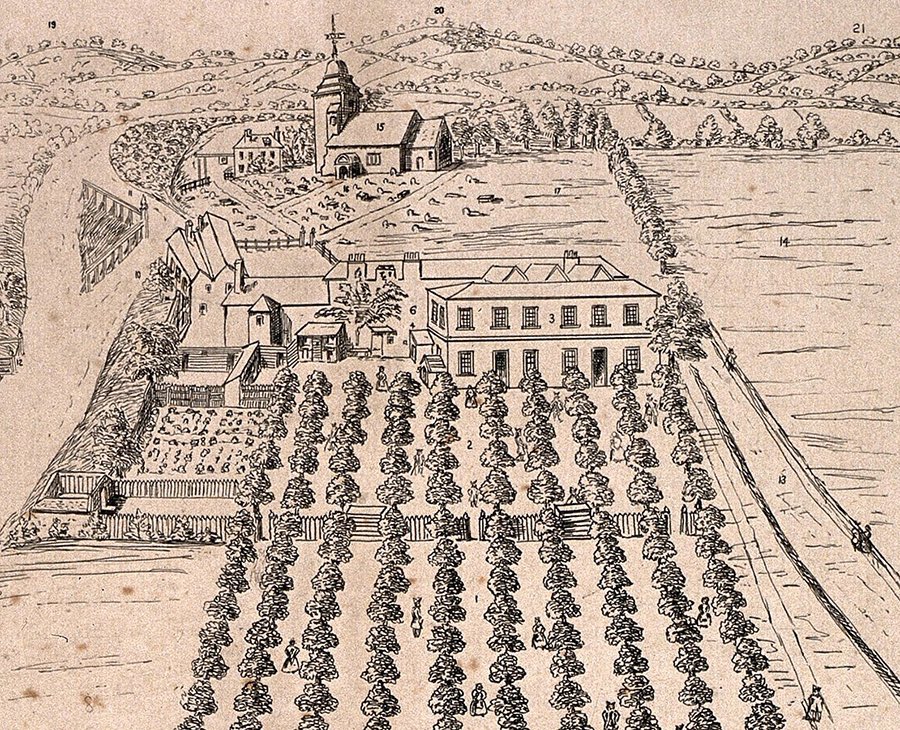

My London #pancrasday route begins of course at St Pancras station – more on that shortly. Along the W side lies Midland Road, built with the station, to the east of Somers Town. The railway development caused this to become a slum. (Map via http://theundergroundmap.com) #pancrasday

The district of St Pancras began as a parish but eventually encompassed dozens of parishes as the population rocketed in the 19th century (now in Camden borough). Swift’s Tale of a Tub is set in Pankridge, a version of the name Pancredge used since the 17th C. #pancrasday

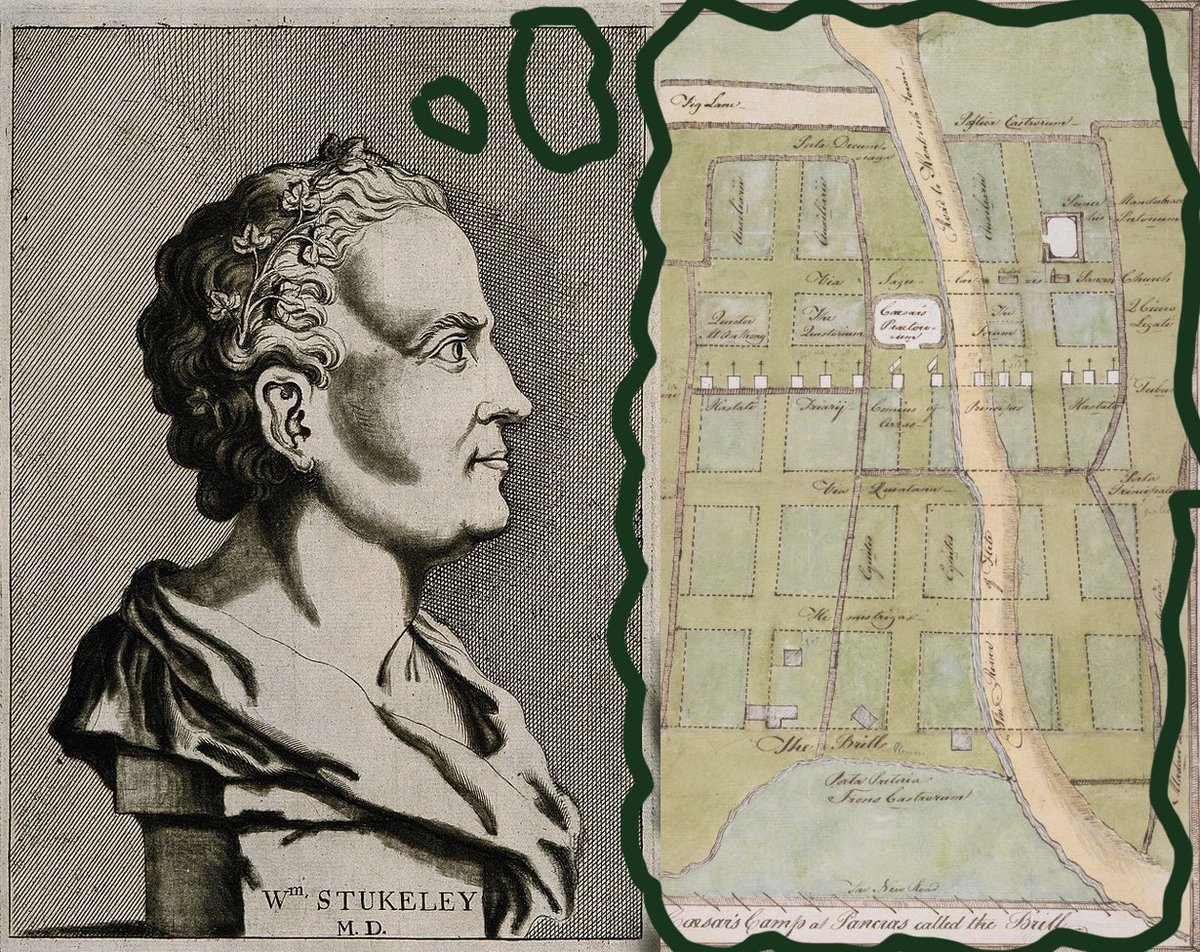

Midland Road passes Brill Place, named for ‘The Brill’, earthworks which in 1750 William Stukeley fancifully imagined was where Caesar had held camp. But there were civil war defences here at Brill Farm in 1642 – and in fact a Roman road passes across here too. #pancrasday

Just W of here was a 15-sided building called The Polygon (demolished 1890), where writer William Godwin and feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft lived – she died in 1797 giving birth to their daughter: later Mary Shelley. Dickens lived here when he was a teenager. #pancrasday

Here’s hope. #pancrasday

Here’s amazing St Pancras Old Church, packed with history I can only touch on. Some have claimed it as England’s oldest but evidence lacks – that gong goes to St Martin, Canterbury, but St Paul’s in London is 7th C. & St Peter-upon-Cornhill could be even older. #pancrasday

St Pancras is at least Norman, and there could be a Saxon origin even. Documents date from the 11th C. and there’s an ancient altar stone (prob. Norman) found during a Victorian rebuild (1848) – plus some Roman tiles. 50 of Cromwell’s men lodged here and made a mess. #pancrasday

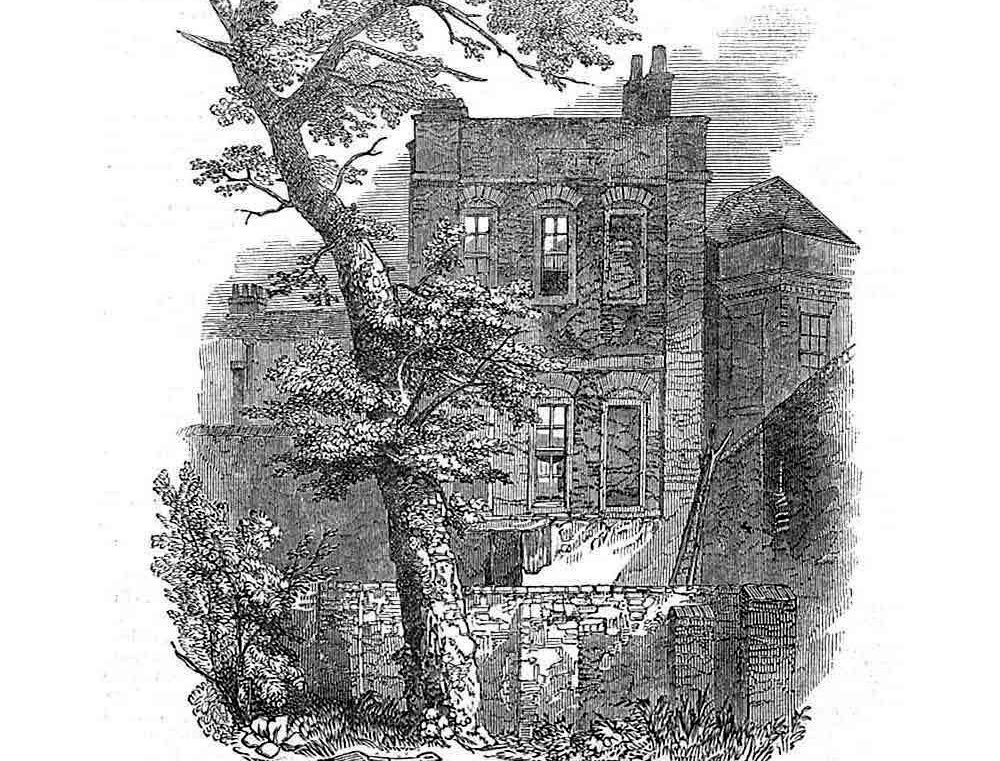

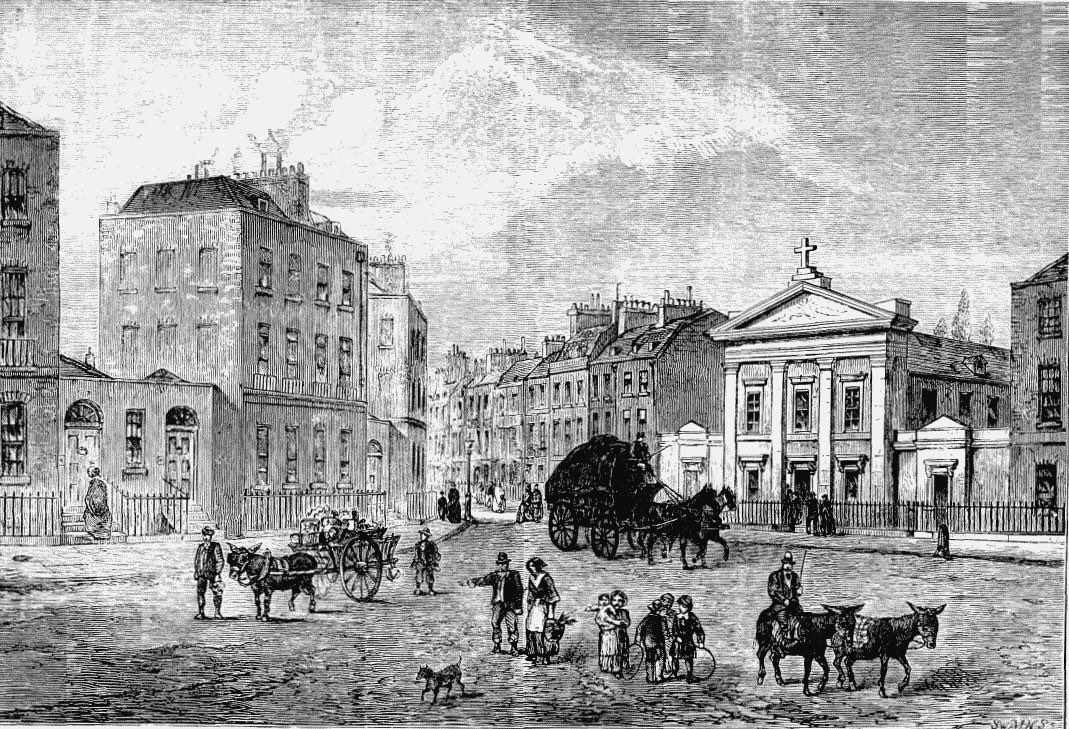

But even by 1593, antiquarian John Norden would write “Pancras Church standeth all alone, as utterly forsaken, old and weather-beaten”. He warned of thieves and said “Walk not there too late”. The church stood beside the now buried River Fleet (pic is from 1815). #pancrasday

The graveyard has many more stories. Shelley canoodled with Mary here. Dickens fictionalised the bodysnatching. Moody poet Chatterton fell into a fresh grave and killed himself 3 days later. 100,000+ burials were made, including refugees from the French Revolution. #pancrasday

In 1803, an extra graveyard for St Giles-in-the-Fields was added: inmates include John Soane, whose tomb inspired the K2 phone box; Byron’s physician J.W. Polidori, author of ‘The Vampyre’, was another, plus Bach’s youngest son, & transgender spy the Chevalier d’Eon. #pancrasday

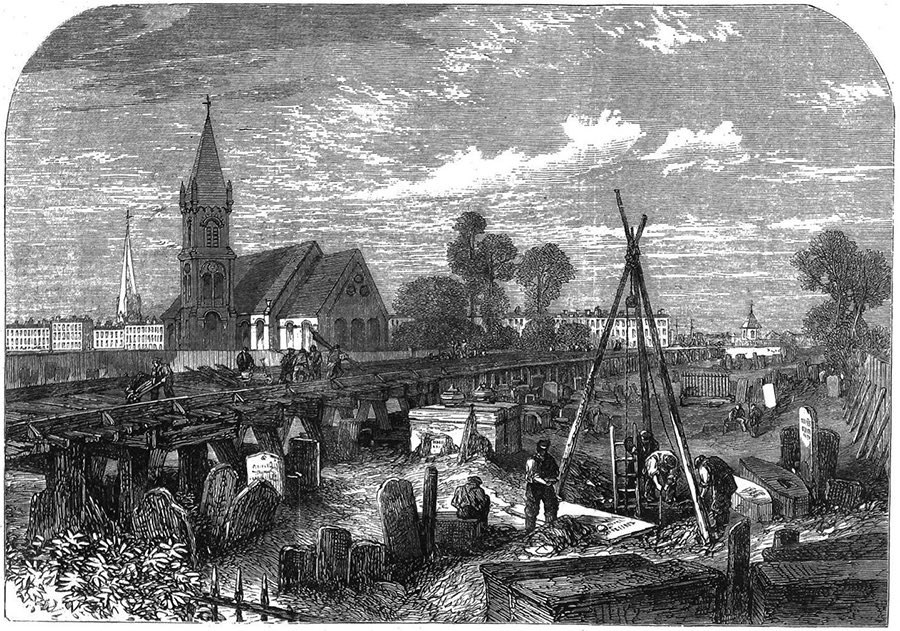

In the 1860s, the Catholic side and much of the St Giles bit was affected by work on the new Midland Railway: many graves had to be moved (an overflow cemetery had already opened up in Finchley in 1854). Contemporaries said it was being “desecrated”. #pancrasday

One workman was trainee architect Thomas Hardy, the novelist. One coffin he found contained 2 skulls. His wife wrote “by the light of flare-lamps, the exhumation went on continuously of the coffins that had been uncovered”. Here’s the Hardy Tree named after him. #pancrasday

St Pancras has long been a lodestone for psychogeographers. If you prefer an alternative take on the Hardy Tree, read this haunting tale by @portalsoflondon: https://portalsoflondon.com/2017/01/20/the-hell-tree-of-st-pancras/#pancrasday

When new work was undertaken for the Eurostar terminal in 2013, a coffin was found containing the bones of eight people… and a walrus! https://www.itv.com/news/london/story/2013-07-23/mystery-of-st-pancras-walrus/ #pancrasday

Now forgotten is Pancras Wells, an 18th C. spa (pictured 1730) just S of the church, and the Adam & Eve tea garden nearby, still a tavern in Victorian times. The wells were “surprisingly successful in curing the most obstinate cases of scurvy, king’s evil, leprosy” #pancrasday

Frustratingly there are builders all over the gardens today so I can’t poke around on the side where Pancras Wells was! #pancrasday [update: see below]

Just N of the church is St Pancras Hospital – previously the 1809 workhouse, later expanded. One inmate was Robert Blincoe, possible inspiration for Oliver Twist. Sign up at https://www.gethistories.com to read my article about him published tomorrow! #pancrasday

Just N of the hospital is Granary Street, named after a huge 19th C. storehouse for 100,000 barrels of beer from Bass in Burton-on-Trent, later used for storing grain. The 1816 Regent’s Canal runs nearby. #pancrasday

And into Camley Street, home to a wetland nature reserve near the floodplain once called Pancras Wash and on the site of old coal yards. It opened in 1985 and was revamped only last year. #pancrasday

The old gasometers in this area were built in the 1850s. They feature in the 1955 Ealing comedy The Ladykillers. I remember taking rubbish arty pictures of them in the 1990s, before they were decommissioned in 2000; some were rebuilt in 2013 in Gasholder Park. #pancrasday

OK, this is why I’m really here… #pancrasday

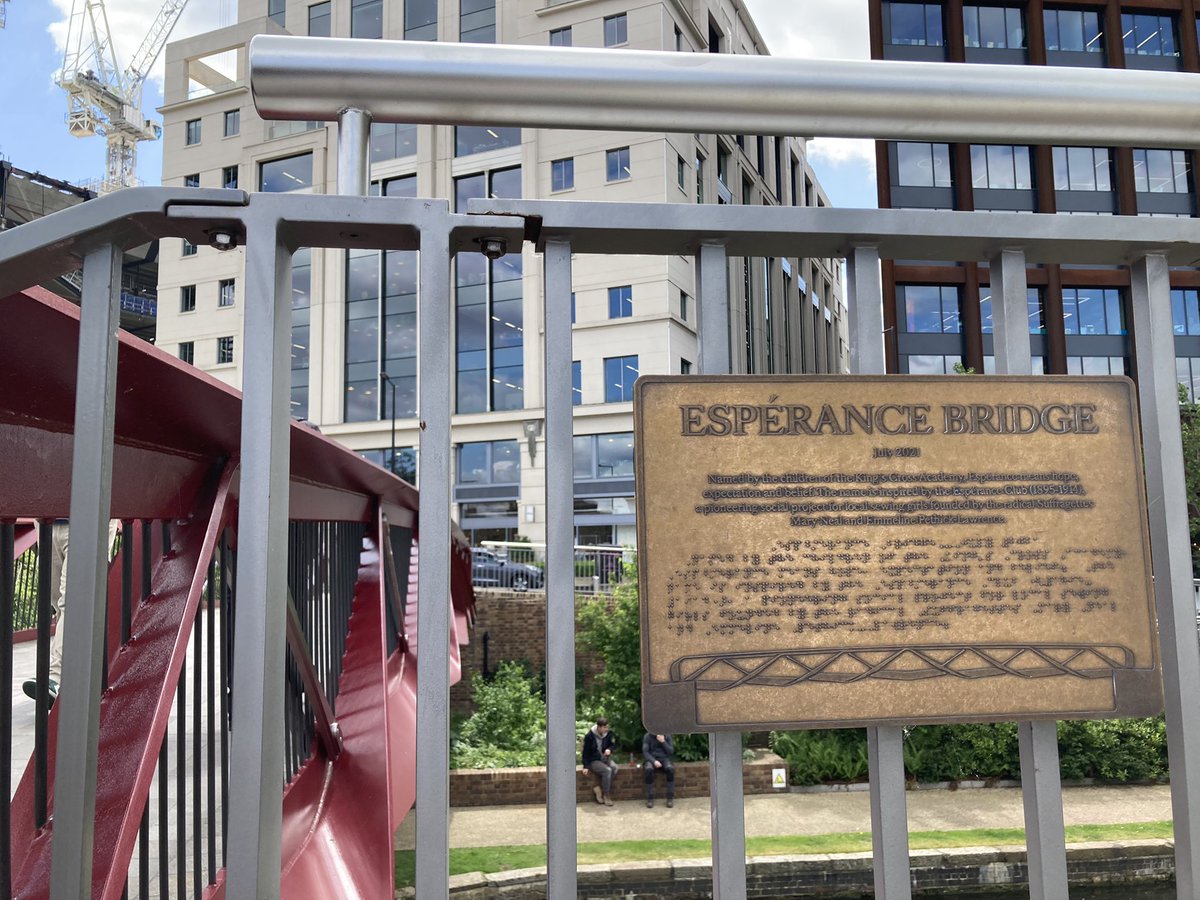

Here’s hope again, and on the Pancras children theme. #pancrasday

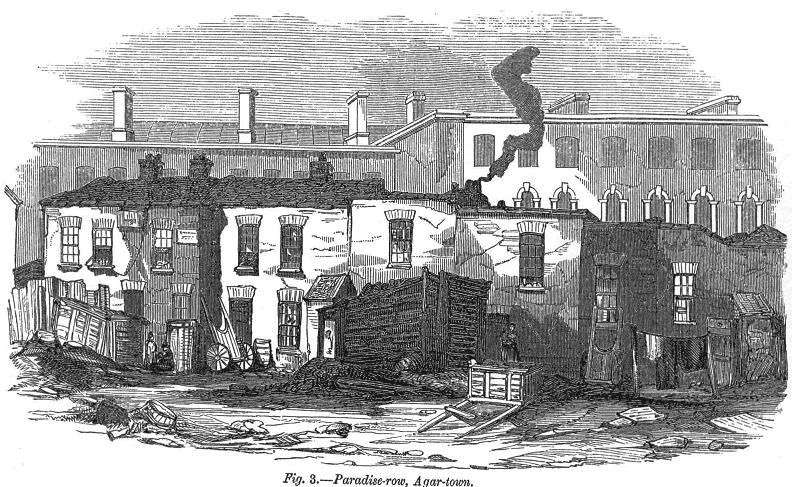

St Pancras station opened in 1868 and the Midland Grand Hotel in 1873. The station site was once Agar Town, a slum named after Councillor William Agar, a Yorkshireman (d.1838) who had a grand villa, Elm Lodge, here. The music hall star Dan Leno was born in the area. #pancrasday

For the next sections of this walk, I’ll be following the route of the River Fleet, which curved past here. Many have written or filmed about it (eg @fugueur) so I’ll only, er, dip in. King’s Cross was once Battle Bridge, allegedly where Boudicca tackled the Romans. #pancrasday

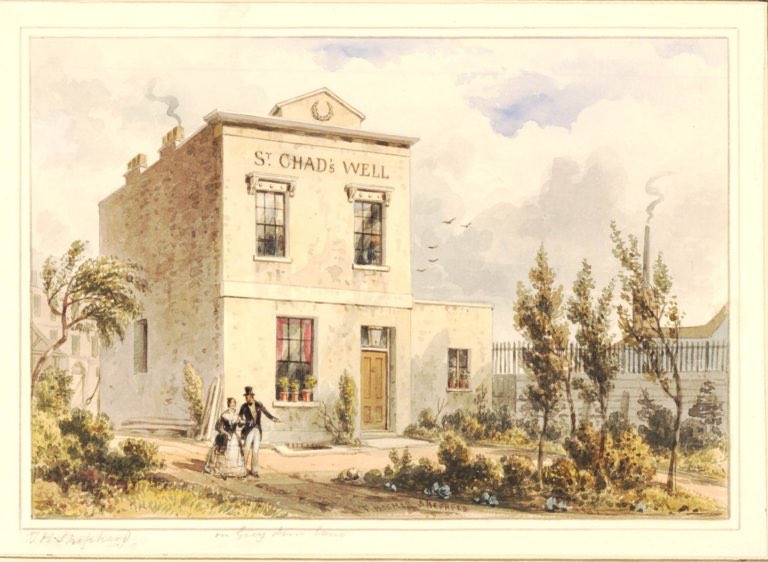

Just off Gray’s Inn Road was once the site of St Chad’s Well, where in 1772 more than 1000 people drank the waters in a week – subscriptions were £1/year. It gradually declined, and the pump room was demolished in 1860 to make way for the Metropolitan Railway. #pancrasday

Another spa site was Bagnigge Wells near King’s Cross Road, then called Black Mary’s Hole. It was favoured by Charles II’s mistress, actress Nell Gwynne. It had a grotto plus bowling green & skittle alley, & 3 bridges over the Fleet. By 1842 it was “almost a ruin”. #pancrasday

As I was passing anyway, of course I stopped at the Postal Museum (@thepostalmuseum http://postalmuseum.org) for a quick trip on the Mail Rail built underground in 1927 for the Mount Pleasant sorting office. Very near the Fleet! #pancrasday

The Fleet also passed the notorious bear garden at Hockley-in-the-Hole, where Ray Street is today. Read my article about it here: https://www.gethistories.com/p/georgian-fight-club-1710 #pancrasday

I can also confirm the rumour you can hear the waters of the Fleet through a grating outside The Coach! 👂#pancrasday

A quick lunch stop at Little Britain feels appropriate, before I’m back directly on the heels of the saint who prompted this. #pancrasday

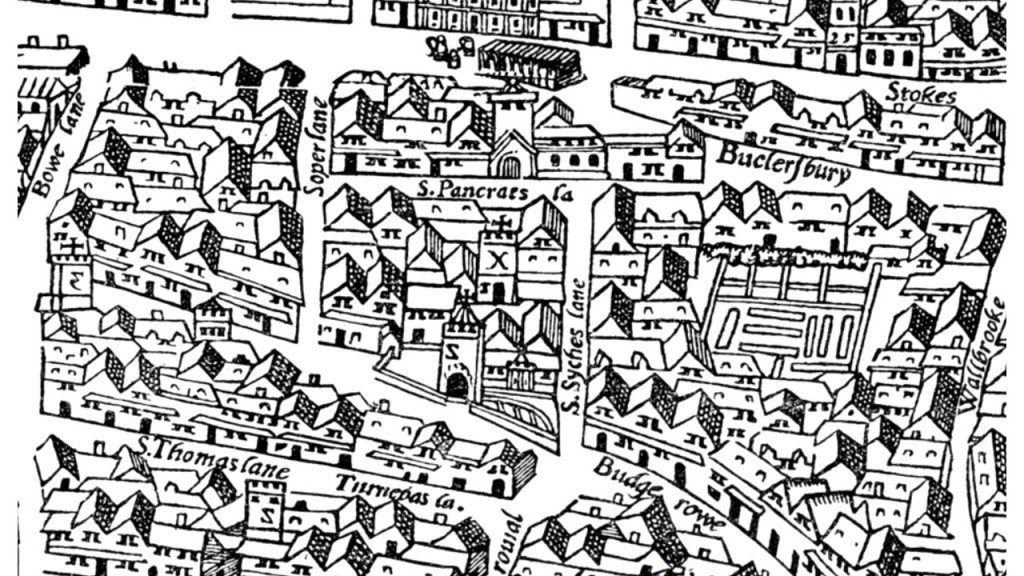

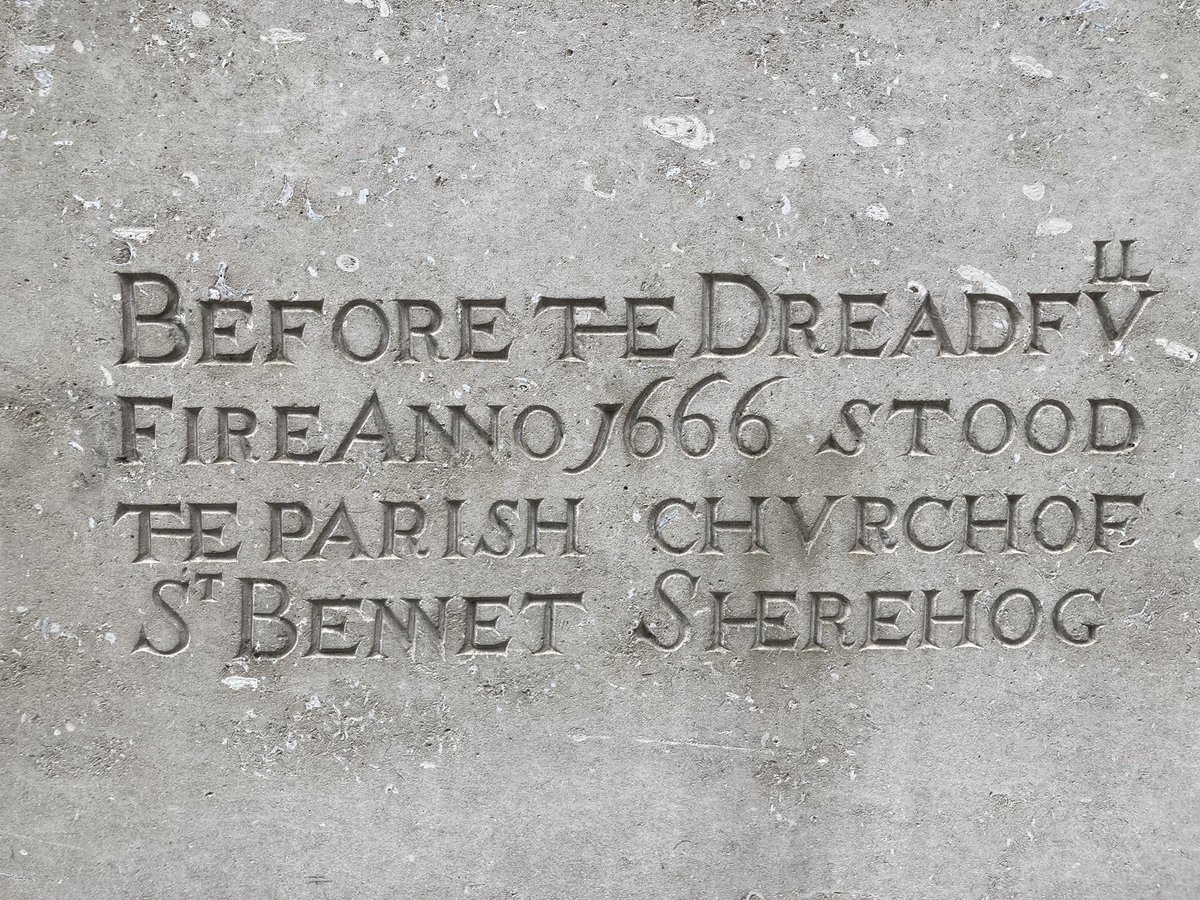

We still have two more London churches named after St Pancras to investigate. Pancras Lane off Queen Street in the City gives a clue to the first. Sadly St Pancras Soper Lane (& its marvellously named neighbour St Benet Sherehog) was destroyed by the 1666 Great Fire. #pancrasday

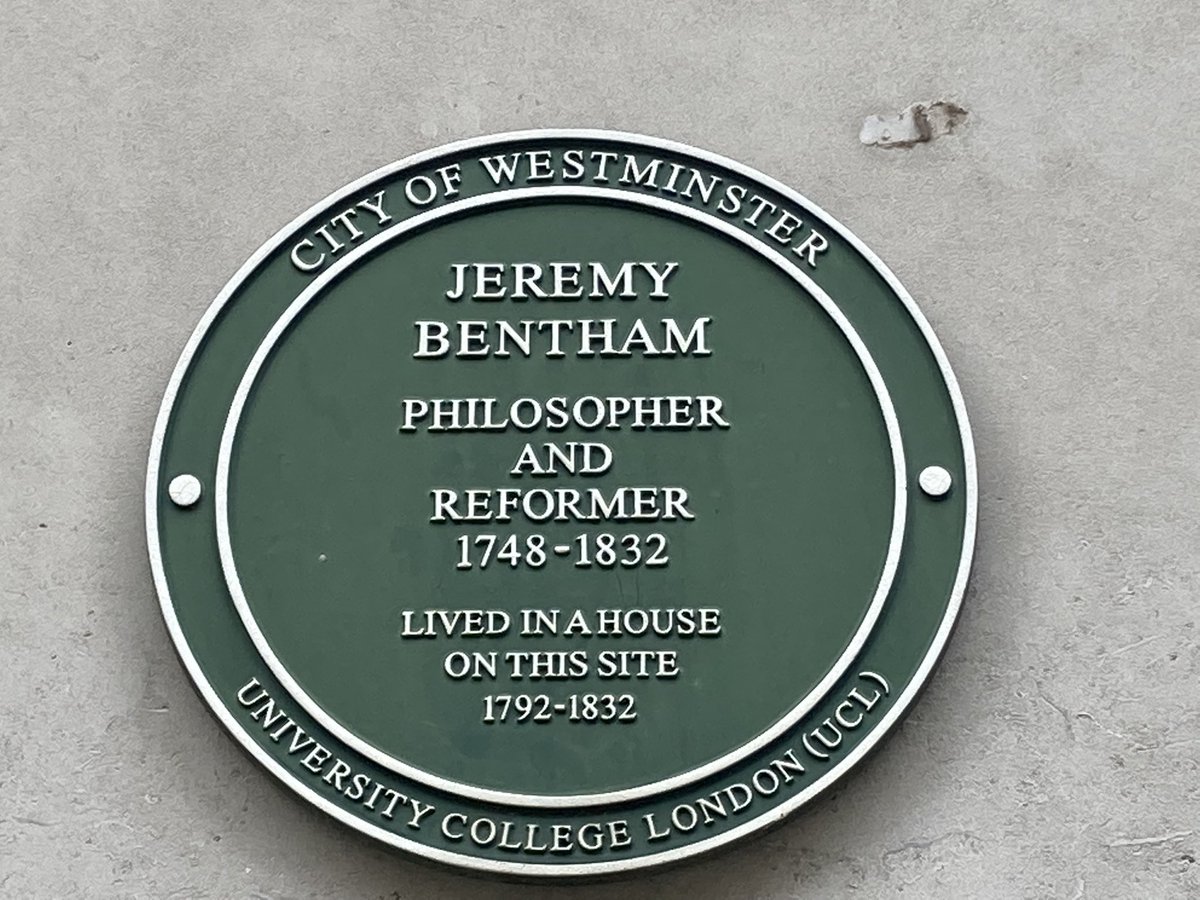

This St Pancras is mentioned in 13th C. documents and was owned by Canterbury Cathedral; it may have been older still. Some remains are buried beneath 70-80 Cheapside – and this little yard marks part of the burial ground (used until 1853) to this day. #pancrasday

In 1374 the archbishop of Canterbury supported the funding of a bell here confusingly called ‘Le Clok’. In the 17th C. a memorial to Eliz. I and repairs were funded by a Thomas Chapman, who I assume is no relation. In 1598 John Stow called it a “proper small church” #pancrasday

Just E of St Paul’s stands the remains of St Augustine Watling Street, tying together the Roman road and the man who brought Pancras to Britain. This Norman church too was lost to the Great Fire, but rebuilt by Christopher Wren. Most of it was lost again in WW2. #pancrasday

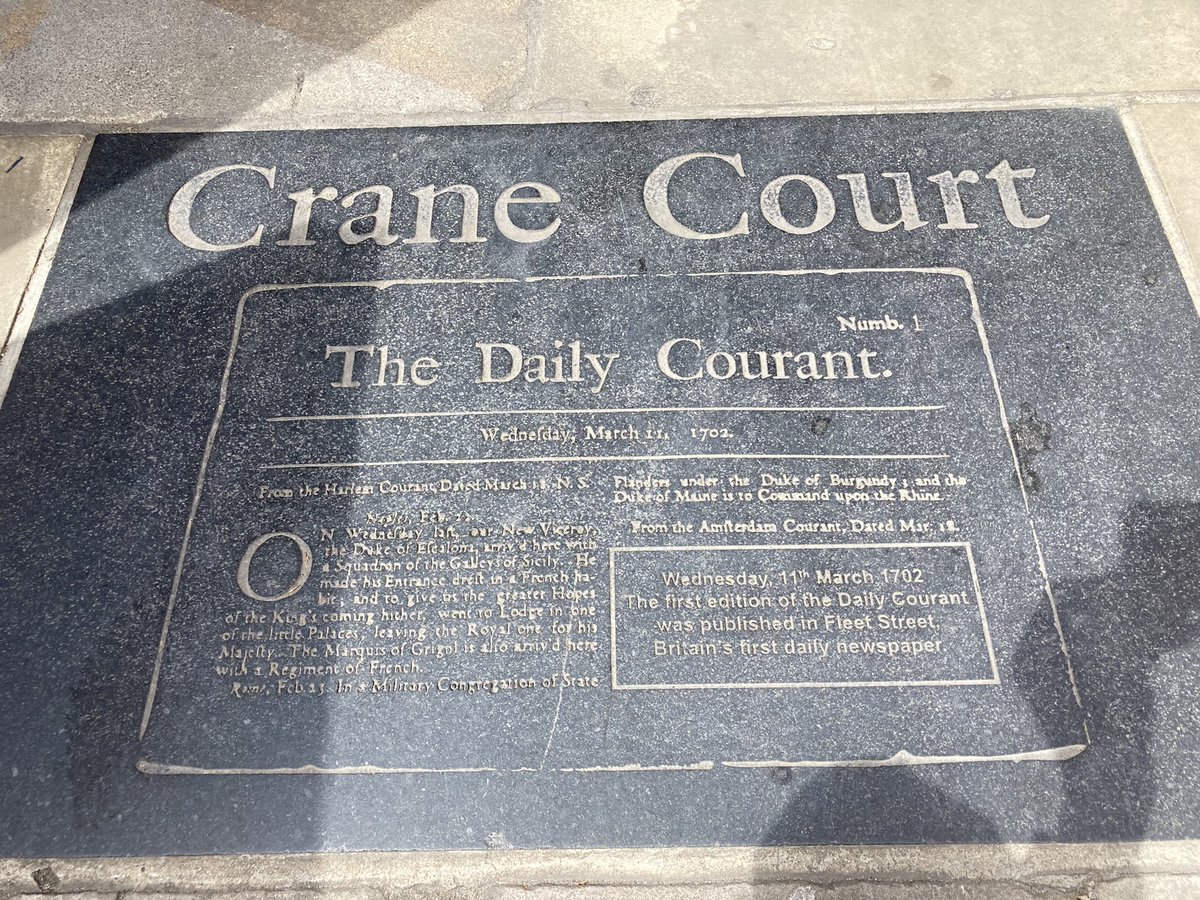

Now I’m heading west along Fleet Street again (see #londonfogg). Here’s Crane Court, where Isaac Newton moved the Royal Society in 1710, and a plaque to Britain’s first newspaper, the Daily Courant. Read my article about that here: https://www.gethistories.com/p/the-first-daily-paper-1702 #pancrasday

At Lincoln’s Inn Fields is the amazing Sir John Soane’s Museum (http://www.soane.org@SoaneMuseum) – as we met him in death at St Pancras, here’s where he dwelt in life. This is the model he made of the same tomb which he kept by his dining table as a memento mori! #pancrasday

Oops – the 6-mile #pancrasday walk has been 9 miles so far…

And finally to St Pancras New Church, built 1819-22 as the main place of worship for the old parish – although it is nearer to Euston. It was inspired by a temple and a tower in Athens. It cost £77,000 to build – the most expensive church since St Paul’s was rebuilt. #pancrasday

The church is known for its terracotta caryatids – female figures serving as architectural props – although they were too big when first installed and to be, er, pruned. Meanwhile the congregation of the old church protested at this one being built. #pancrasday

(A volatile vestry meeting in Southampton Tea Gardens “was very tumultuous” and a punch was thrown – and at the 1819 stone-laying ceremony “a numerous gang of pickpockets rushed in”. All good fun. #pancrasday)

And on that nefarious note, my #pancrasday walk comes to an end. Thanks for following! (I have plans afoot for historical walks outside London, if you like this sort of thing, and do sign up to my weekly newsletter, https://www.gethistories.com)

Follow-ups

- My article on ‘the real Oliver Twist‘ (a memoir of an inmate at St Pancras workhouse).

- 3/6/22: On my #pancrasday day adventure a few weeks ago I couldn’t see all of Old St Pancras churchyard due to work going on. I’ve snuck back to visit the corner near where the Pancras Wells resort was, thanks to a sexton letting me through the barriers. Anyone for dominos?

Around the World in Eight Hours

In search of Colin’s Barn (aka The Hobbit House)

Some blundering around on the internet recently led me to read about an extraordinary place known as Colin’s Barn, or The Hobbit House (not to be confused with a self-consciously titled eco-home of the latter name built in Wales). I had to find it, so a small but intrepid band of us sallied forth to track it down. Briefly, it was built between 1989 and 1999 by a stained glass artist called Colin Stokes, on land he owned near his house in Chedglow, Wiltshire. He built it for his sheep. Apparently the council were not best pleased that neither Stokes nor his flock had been through the due planning process, and the stress of the bureaucracy may have contributed to him moving to Scotland. The ‘barn’ remains quietly dilapidating in a field.

There’s plenty more at Derelict Places but with care to keep its location secret. I’m not going to blab either, but suffice it to say (a) that it’s on private land, so tread warily and respectfully (b) despite what commenters at that site and others say, it can be found on Google maps, rather easily if you use your brain and (c) all of the stuff on these forums about rottweilers and security heavies appears to be twaddle. Or perhaps they are otherwise occupied on sunny afternoons. My only hint is to follow the horses and not the cars. (More photos at Flickr.)

Anyway, it’s a beautiful and amazing thing – and maybe the world is a better place for things like this being left dotted around in quiet corners.

Walking the River Effra

A guided route, based on a walk in 2002, following the route of London’s lost River Effra.

This is an attempt to follow the route of the Effa river as close as possible – the river itself was once comparable to the Fleet north of the Thames, although sources differ over the upper part of its course, and it seems to have had various branches in the Norwood area. One thing that walking the route does, however, is let the folds of the landscape speak for themselves: the best source is the river itself.

The Effra was already being used as a sewer by the 17th century, although the upper reaches were still clear in the second half of the 19th. Even today, a stretch is perhaps visible – as the following walk reveals.

The walk begins at one of the likely sources of the river: somewhere in Upper Norwood Recreation Ground. This was acquired by Croydon Council in 1890 from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for about £6,500; two new roads, Eversley and Chevening, were constructed. The site offered a view of the Crystal Palace towers and included one of the head waters of the Effra, running north-west.

Walk along Chevening Road westward to Hermitage Road. According to legend Queen Elizabeth I came up the river in her barge to where Hermitage Road now stands – though it is extremely unlikely that the river was actually broad enough here, so near to the source.

The area north of Hermitage Road is known as Norwood New Town – apparently a bridge made of four planks used to run across the Effra stream somewhere here. Walk up Hermitage Road and on the left past Ryefield Road is a small cul-de-sac: walk down here and at the end is a drain in the road with water rushing loudly underneath. Could this be the lost call of the Effra?

The river ran through the grounds of what is now the Virgo Fidelis convent school – not open to the public, of course. But the river makes itself known just the other side. Walk up Hermitage Road and turn left: the dip of the river valley is very distinctive where Elder Road meets Central Hill. The brick wall of the convent was swept away on 17 July 1890 when the river and West Norwood flooded – damage is still visible in the convent wall.

Heading north up Elder Road, on the south side of the old relieving office (on the left hand side of the road) a stone tablet indicates the level that the flood reached in 1890.

On the right is Norwood Park: once upon a time there were thatched cottages here, whose inhabitants had to cross the stream by little wooden bridges to get to the road. There used to be iron gratings in the fields where small boys would drop paper boats. At the end of Windsor Grove, there used to be two large ponds known as ‘The Reservoir’. Meanwhile, to the west, in the 20th century the bed of a tributary could still be seen at the back of the tennis courts at the bottom of Cheviot Road, which is likely to have belonged to a tributary of the main river.

Walking further up Elder Road into Norwood High Street, East Place, on the right just before the railway line, is another flood site: on 14 June 1914 the former river overflowed from the brick sewer imprisoning it and the ground floors of many West Norwood houses flooded – it is even claimed that some people’s Sunday joints were washed out of their ovens. Animals were also trapped in the floods in East Place in the 1920s.

The river bends right here and heads through West Norwood Cemetery somewhere. In 1935 the sewer was enlarged to help avoid the repeated floodings, and deep shafts were sunk in Norwood High Street, Chestnut Road and Rosendale Road. Again the landscape in this area suggests at least a rough course for the river.

From Norwood the river is generally agreed to have followed Croxted Road up to Brockwell Park: turn right into Robson Road past the cemetery, up Rosendale Road, into Carson Road on the right and then across to Croxted Road to get a rough idea of where the river ran. Evidence from flooding cellars suggests that the course of the river may actually have been west of Rosendale Road rather than Croxted Road.

Before heading north, though, a detour: cross Croxted Road at the crossroads going past West Dulwich station, and turn north up Gallery Road. On the left is Belair Park, which contains an ornamental pond which some say is part of the Effra visible still. Some say it was a tributary of the main river. There was also a millpond in this area. A cast-iron chimney opposite Dulwich Picture Gallery is believed to vent the tributary here.

Here you can either retrace your steps to Croxted Road – if you believe Belair’s pond to be a tributary – or continue north and cut back across to Herne Hill via Burbage Road, named after Shakespeare’s actor contemporary. Another actor, Edward Alleyn, founded nearby Dulwich College.

Another tributary is said to supply Dulwich Park Lake, flowing down from the woods of Sydenham Hill, alongside Cox’s Walk and under Dulwich Common. A local resident reports that in wet weather this rises above the drains and flows along the road around Dulwich Park by Frank Dixon Way.

The 19th century painter and critic John Ruskin, who grew up in Herne Hill, said that his first sketch showing any artistic merit was at the foot of Herne Hill, showing a bridge over the Effra.

Again the precise channel of the river is under dispute, or at least there may have been tributaries meeting here, coming from Knights Hill in the south and along Half Moon Lane to the east, marking the edge of Joseph Bazalgette’s sewer network in south London. As with Belair, there is an ornamental pond (late Victorian) in Brockwell Park said to connect to the Effra, perhaps as yet another tributary. A woman at 32 Tulse Hill in 1891 described a stream that had flowed across the end of her garden, and said that the banks could still be seen in Leander Road.

Opinions and tributaries rejoin to the north of Brockwell Park: the name of Effra Parade gives a helpful clue – though for the walk it is probably more helpful to take the next road on the right, Barnwell Road, then head northward again up Rattray Road. At the top, turn left and join Effra Road going up into central Brixton – though an unexplained rise along the west side of Dulwich Road suggests that perhaps one ought rather to follow this and Brixton Water Lane, thence all the way up Effra Road.

Along Brixton Road, the course of the Effra is more certain, and wider. Its average size was said to have been 12 feet wide and 6 feet deep. Bridges gave access to the houses on Brixton Road, with the river flowing on the east side. A bomb fell at the corner of Angell Road and Brixton Road during the Blitz, uncovering the Effra sewer. It’s hard to imagine now, but a 1784 painting shows St Martin’s Farm with the river passing by – the site is where Loughborough Road now branches off. As well as Queen Elizabeth, Canute is said to have sailed up the river as far as Brixton – and King James I gave permission for the river to be opened up for navigation in this area.

At the top of Brixton Road, turn left and head across to the Oval, following its left-hand side. This is Kennington, once an area of marshland. Brixton Road originally crossed the river at Hazard’s Bridge, marked on a plan of Vauxhall manor from 1636. The Effra divided the manors of Kennington and Vauxhall.

This area was built over between 1837 and 1857. St Marks’s Kennington paid ¬£322 towards the costs. The raised banks of Oval cricket ground were built with earth excavated during the enclosing of the Effra, which nevertheless showed itself again and was apparently responsible for ‘a small inundation’ at the Oval in the 1950s. South London Waterworks (founded 1805) used water from Vauxhall Creek, the name of the river (or a tributary) along this stretch, though it soon accumulated rubbish; the Oval gasholder is on the site of one of the reservoirs.

Heading west, the river is believed to have had two entries into the Thames (shown on a 1795 map): one just south of Vauxhall Bridge, the other nearer to Nine Elms Lane. In 1340 the Abbot of Westminster had to repair Cox’s Bridge (Cokesbrugge) over the Effra near present day Vauxhall Cross (Kennington Lane/Wandsworth Road/South Lambeth Road). There was another bridge over the creek on Clapham Road (Merton Bridge – the responsibility of Merton Abbey). In 1504 another Abbot of Westminster paid rent for a wharf at Cox’s Bridge – in the 17th century maintenance of the bridge caused a dispute. The lower river was a sewer by the 17th century, labelled as such on the 1636 plan.

The Fort at Vauxhall erected to defend London during the Civil War was alongside the Effra – as shown in a drawing (though this is perhaps a forgery of the mid-19th century). A gardener ‘recently deceased’ in 1895 recalled the Effra at Lawn Lane ‘wide and deep enough to bear large barges’.

Lawn Lane is still there: follow the back streets south-west of the Oval, across to Parry Street, and brave the traffic across to Vauxhall Cross. Peer into the Thames here – and you can see a sewer outflow which may be the last remains of the Effra’s mouth.

Further reading

- Barton, Nicholas – The Lost Rivers of London (1962,1992)

- Coulter, John – Norwood Past (1996)

- Foord, Alfred Stanley – Springs, Streams and Spas of London (1910)

- Trench, Richard & Hillman, Ellis – London under London (1984,1993)

- Wilson, J B – The Story of Norwood (1973,1990)

“The Minster is very large and fine of stone, carv’d all the outside 3 high towers above the Leads”

“I was in one of them, the highest, and it was 262 steps and those very steep steps” [the Minster says 275 and I made it 281!]

“On the Leads of the tower shews a vast prospect of the Country at least 30 mile round, you see all over the town that looks as a building too much cluster’d together, the Streets being so narrow, some were pretty long.”

“In the Minster there is the greatest curiosity for Windows I ever saw they are so large and so lofty, those in the Quire at the end and on each side that is 3 storeys high and painted very curious, with History of the Bible”

“There is a large hunter’s Horn tipped with silver and garnish’d over and engrav’d finely, all double gilt” [a copy shown – ironically the original is on holiday in Oxford where I came from today]

(The Horn of Ulf is currently part of this exhibition: https://visit.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/event/gifts-and-books @bodleianlibs)

“The Chapter house is very finely carv’d and fine painting on the windows all round, it’s all arched Stone and supported by its own work having no pillars to rest on”

For the full story, read my Histories newsletter 😁 https://www.gethistories.com/p/the-mean-streets-of-york-1697