This is a longer account of a personal pilgrimage from London to Canterbury in August/September 2024, which I gave a version of as a talk at the 2024 Fourth World Congress of Psychogeography (a video is here). I have also written connected articles about the death of Thomas Becket and the last pilgrim to visit his shrine before it was destroyed in the Reformation.

Where do you think of as ‘home’? Where are you ‘from’? Where do you feel you belong, or should belong?

I’ve often wondered about these things – I’ve lived in more than 30 houses, across Wales, Scotland and eight counties of England. I’ve spent the last 20 years in Oxfordshire, raising a family and putting down new roots, but have no old roots there at all. Where I do have roots in East Kent. I went to secondary school here in Canterbury and lived in the city for some of that time. My parents between them had roots in Ramsgate, Sandwich, Folkestone, Sittingbourne… Is this where I’m from, then?

A year or so ago I started having nostalgic pangs for Canterbury, having been here only rarely in the last 30 years, and had decided to make a personal pilgrimage from London – I know I’m not exactly the first person to think of doing this!

But which route? The obvious, bucolic one would be the one known as the Pilgrim’s Way. This goes from Winchester to Canterbury, but there’s a spur from London known as the Becket Way. However, this is basically a Victorian invention – with a neat twist of nominative determinism, in 1855 a man named Albert Way proposed the route, which was then picked up slightly too eagerly by the Ordnance Survey and then popularised by writers such as Hilaire Belloc. There’s scant evidence that real Canterbury pilgrims used it – though it certainly follows prehistoric ridgeways such as the Harroway in Hampshire and over the North Downs.

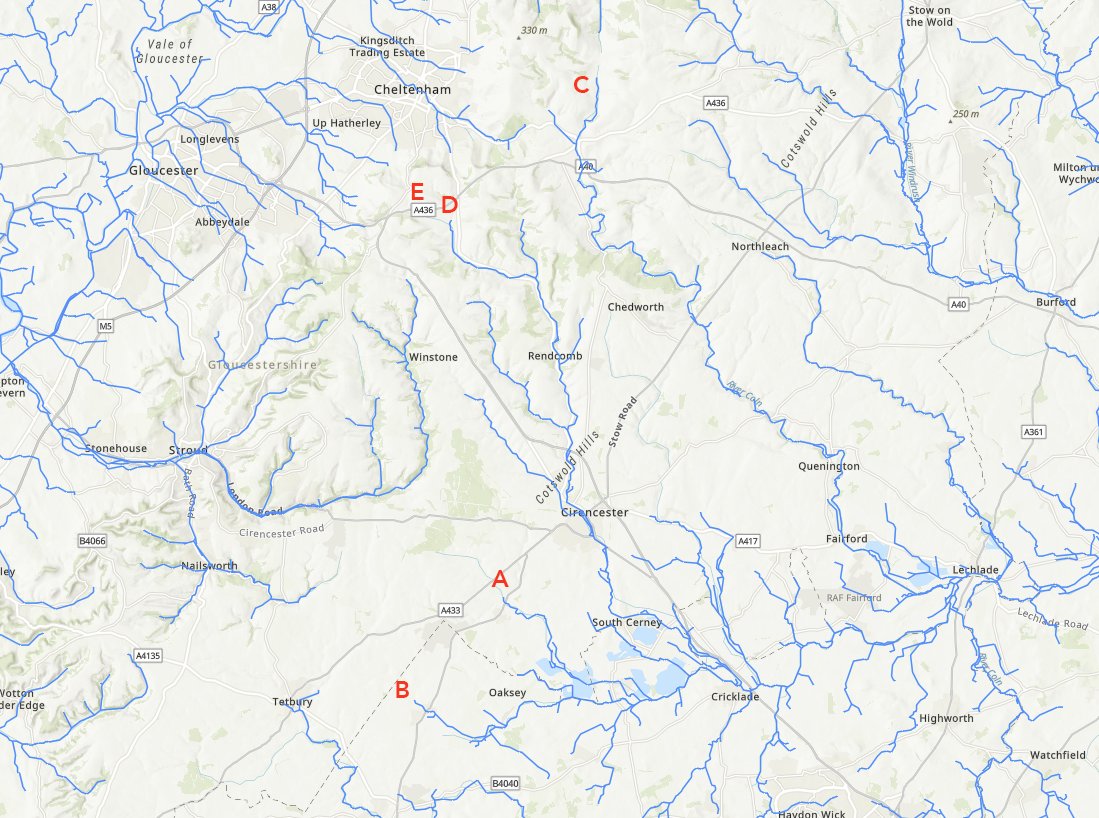

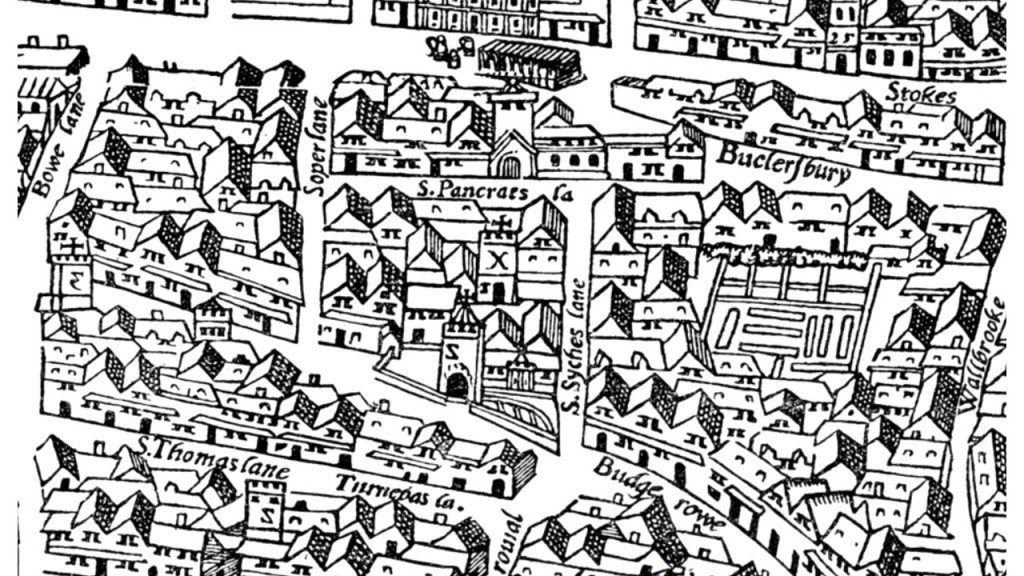

Chaucer gives us better clues to where pilgrims from London actually went. He only mentions seven places between his starting point in Southwark and Canterbury but here they are on a map: the route is very obviously along the Roman road we call Watling Street. That too is a misnomer, but we’ll come to that. In 1360, only a couple of decades before Chaucer’s pilgrims, King John the Good of France took this route to Canterbury and it is well attested. On my map here in blue, sacred springs, wells and waterways once dedicated to St Thomas; and in purple, churches and chapels likewise.

In his book Watling Street, John Higgs says, “Watling Street is a road of dreams, imagination and stories, especially on this stretch from London to Canterbury”. So I went in search of those stories – those I found are completely different from the ones in his book, and I’m sure there are many more to tell.

In the end I did this as five walks, not on consecutive days but all in the last month, the very last leg being the day of my talk. This was a chance to explore the history of the route and places along it, as well as some personal places in search of a feeling of home. But following the A2 almost all the way made for something of a grim challenge!

1. Southwark to Greenwich

This was my shortest walk, because both of my children came with me on a very hot day, wooed by the promise of the Lego store on the way back. Like any London walk it is dense with history.

It starts in Southwark. Thomas Street at the back of London Bridge marks the site of the original hospital founded in martyred Becket’s honour. Off Borough High Street is the site of the Tabard Inn, where Chaucer’s pilgrims began. The inn has long gone, although the neighbouring George Inn at least gives a flavour of the place in later Elizabethan times. I used to drink here and elsewhere nearby when I lived in London.

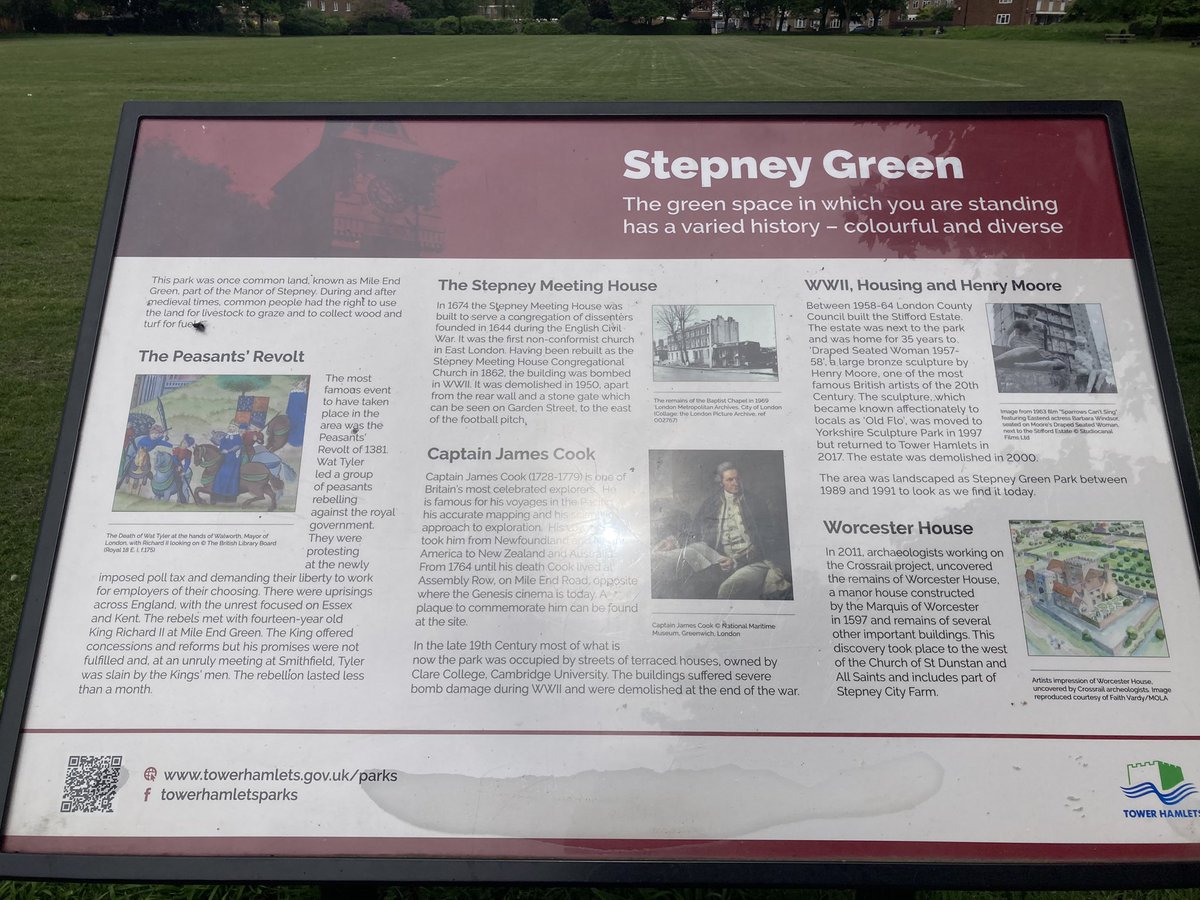

Down the street is the site of the old Marshalsea Prison, which was ransacked by Wat Tyler and friends in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 (a theme which will return). Further down it is a wall which is the only surviving vestige of the later iteration of the Marshalsea, where Dickens’s father was imprisoned in 1824.

The church of St George the Martyr at the bottom of the street marks where Roman Watling Street and Stane Street met. It’s where Henry V was welcomed in triumph by the aldermen of London after his victory at Agincourt, having travelled along Watling Street from the Kent coast.

Down Tabard Street, along the ancient Roman alignment, and into Old Kent Road. A little way along is the first place Chaucer mentions on the route: the Watering of St Thomas. This is a place of echoes and ghosts. It is where the horses were given water from the Earl’s Sluice, now a ‘lost London river’ – you can still see the dip in the road, and the lake in nearby Burgess Park is fed by the same source. Henry V was welcomed by London’s clergy here. After the reformation (when all thought of pilgrimage was banished), religious dissenters were hanged here. From the 19th century, perhaps earlier, the Thomas à Becket pub stood here, and was said to be haunted. During Jack the Ripper’s rampage, a mysterious bag full of knives and scissors was abandoned here. In the 1950s, boxing champion Henry Cooper trained here for many years, visited by Muhammed Ali and Darth Vader David Prowse. A few years later, David Bowie rehearsed Ziggy Stardust here. After numerous incarnations, the pub has gone – but look, here the gaunt face of Thomas Becket hovers still.

Further along, here’s Polish artist Adam Kossowski’s 1965 History of the Old Kent Road, left gathering dirt on the wall of the old North Peckham Civic Centre, now the Everlasting Arms church. It hints at many of the stories of the road, some of which we’ll return to. Remains of Watling Street have been dug up in gardens nearby.

Onward down through New Cross and Deptford – the ‘deep ford’ where the Romans crossed the Ravensbourne. In 1895, travel writer Charles Harper snarked that ‘The Deptford of today is no place for the pilgrim’ – but I disagree, as we pass the ghosts of Christopher Marlowe and where Peter the Great trashed John Evelyn’s garden.

And so this first walk ends at a roundabout in Greenwich Park, with General Wolfe and St Anne’s Limehouse aligned one way, and Blackheath church the other. In a short film about this bit of Watling Street made by John Rogers, Iain Sinclair said, ‘The start of my whole writing-about-London project was here… it’s one of the most significant spots in the whole city [with] incredible alignments which represent lines of desire and lines of force’. You have to ‘feel it in the soles of your feet’, he says. Something you don’t want to feel in the soles of your feet is Lego, but that’s what took us away from the ancient path.

2. Greenwich to Dartford

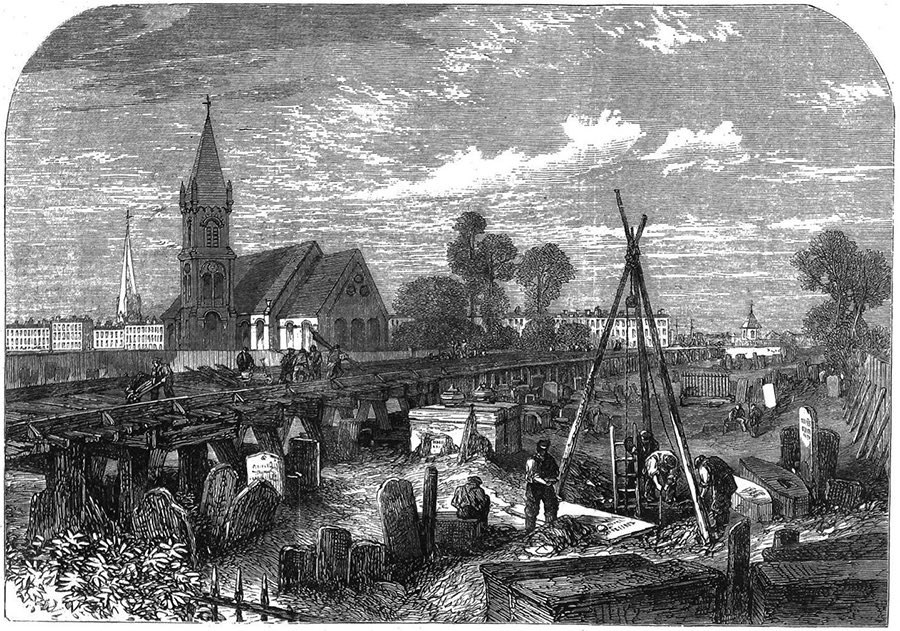

Greenwich Park has one of the country’s most important Anglo-Saxon barrow cemeteries – pictured here in 1844 but still visible. Roman Watling Street slices across the flower garden before heading over the edge of Blackheath, where rebel commoners Wat Tyler and Jack Cade assembled their forces in 1381 and 1450, and on up Shooter’s Hill, haunt of highwaymen.

But here I took a detour, now just with my 15-year-old son, down through ancient woods into New Eltham. This is the house where I lived for a year in the 1970s (a photo records me in a silver jubilee union jack hat, which I can still remember hating). It’s the house where my mother was born in 1930 and which my grandparents owned for more than 50 years, and here’s the school she went to, as did I for that year. I was lonely there, so this doesn’t feel like home. A mile away back towards Watling Street, my grandparents’ grave (inscribed in 1966 and 1984) – already hard to find, hard to read.

Back on the Roman route to Bexleyheath, where Chaucer-obsessed William Morris built his Red House in 1860 as close to Watling Street as he could, up and over the curious detour still called Old Road in Crayford, where the Romans abandoned the line to climb the hill, and into Dartford.

Dartford is one of numerous places claimed to be where the revolting peasant Wat Tyler was born, and it is certainly where he and his men passed – like Henry V only 34 years later, they came this way from Canterbury, although in their case it was to murder another Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon Sudbury, rather than honour one. Jane Austen also travelled to Canterbury and stopped in an inn nearby. In the lane pictured here, Watling Street hints at itself in a hump in the road. And here too is Holy Trinity Dartford, which had a chapel dedicated to St Thomas. Dartford had a foundry where pilgrims’ badges were churned out, and the town took a big economic hit when Henry VIII stopped it all. End of walk 2!

3. Dartford to Rochester

And so into the edgelands, one weary son still with me, past the modern pilgrimage site of the Bluewater shopping centre. Poet Dan Simpson followed Watling Street 10 years ago but described this section alongside the multi-lane A2 as ‘unwalkable’. Challenge accepted.

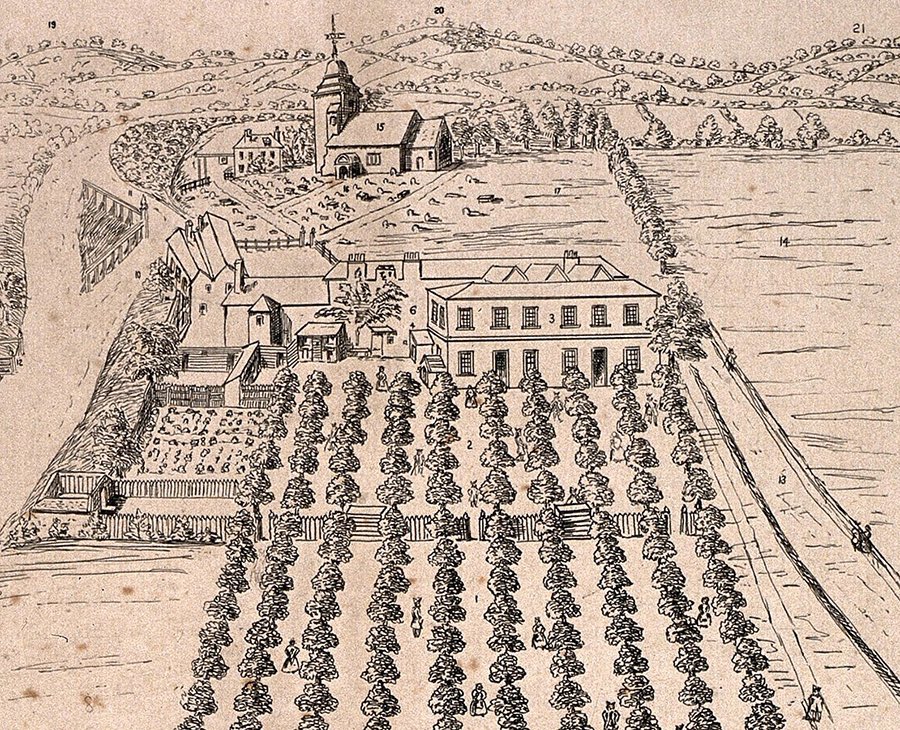

From Bluewater to sacred water. This section is punctuated by ancient springs and wells. Just before the confluence of Watling Street and the High Speed 1 rail line used by Eurostar is Springhead, where eight springs form the source of the River Ebbsfleet and the Romans built Vagniacae, a complex of around a dozen temples. And here in 1805, a man named William Bradbery started Britain’s first commercial watercress farm – a later owner added a small zoo, fortune tellers and other gimmicks like a modern garden centre, and there’s still a nursery here today.

Passing south of Gravesend, along here were Singlewell and then the Well of St Thomas; tantalisingly both survived until the 1950s but we could find no sign of them now, and took a detour to Cobham for lunch. This is the Leather Bottle inn – its very name describing one of the key accessories for medieval pilgrims. Dickens immortalised this pub in the Pickwick Papers. A few years later, artist Richard Dadd was convalescing in the same street. He was five years younger than Dickens and both spent their formative years in Chatham and Rochester, but only Dadd was possessed by the Egyptian god Osiris. One day in August 1843, Dadd took a walk with his father – Dadd’s dad, if you will – and stabbed him to death in Cobham Park under the god’s orders. Dickens later took his friends to the spot, which became known as Dadd’s Hole, which my son and I unwittingly passed right by on our walk. On 7 June 1870, obsessive walker Dickens went for his very last walk here in Cobham Park – two days later he was dead.

And so to Rochester and its cathedral, which has a flight of Pilgrims’ Steps. These footworn steps once took pilgrims to the shrine of St William of Perth, himself a humble baker once a pilgrim to the Holy Land and murdered in 1201.

4. Rochester to Faversham

Walking, alone now, through the high streets of Rochester and Chatham offered me a microcosm of the contradictions of Britain: the former is heritageland, with Rochester’s grand castle, focal point of many battles but finally pillaged by Wat Tyler’s crew, the country’s second oldest cathedral, and enough Dickensian flummery to fill a theme park. But the tourists don’t reach Chatham High Street, a multicultural place with Romanian corner shops, a busy synagogue and all too many people sleeping rough.

The Roman road blasts onward though. Here at Newington, Becket himself visited on his last journey to London, leaving, so it is said, miracles in his wake. And we have a mystery tomb: this is held to be the shrine of St Robert of Newington, possibly another murdered pilgrim. And this could be only one of three shrines in Britain where a saint’s relics can still be found, one of the others being Westminster Abbey. Robert probably died in 1350, and the church also has 14th-century wall paintings.

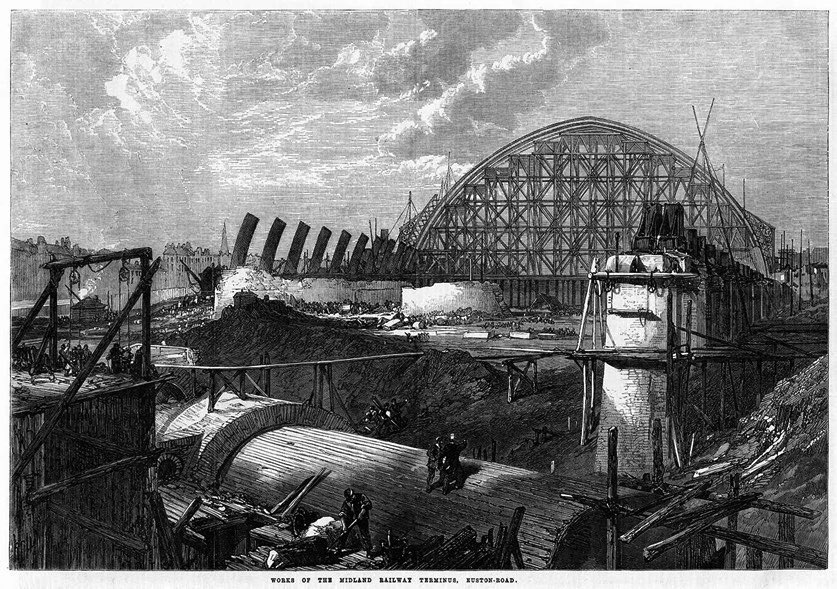

Meanwhile, in 2019 a Roman temple was found during the creation of the new Watling Place housing development – this reconstruction 70 metres away was only built in 2021. Two fields away is Keycol Hill, once known as Crockfield because of the sheer number of finds from a huge Roman cemetery here – I found possible Roman pottery myself. The name Keycol appears to be a corruption of Caii Collis – Caesar’s Hill. And the next place we reach is Key Street. This village was mostly obliterated by road developments for modern traffic in the 1980s and 1990s, and a forlorn and lonely history board stands at the roundabout here. But Key Street is the true name of Watling Street too – the Waeclingas were the folk of St Albans, nowhere near here, but in Saxon and Jutish times this was actually Caising Street – Caesar’s Road. The key street. This modern street name is all that remains to mark this.

The street passes straight through the heart of Sittingbourne, where there were more medieval chapels seeking alms from passing pilgrims, and on to Bapchild, home to the Spring of St Thomas. See the modern echoes here, in a new housing estate and the Bapchild wastewater pumping station. I trekked across a field to find the boggy remains of this key saintly site.

The next settlement is Teynham now, but until the 1940s this part was called Greenstreet, weirdly erased from the map and from the place, other than a Methodist church name. I took a two-mile detour to Lynsted, where my great-grandmother Eliza Allsworth’s family came from. Her chest of drawers sits in by bedroom today. I found family graves here – was this home? I felt nothing, having no real-life connection here. But after this walk I did find that one of Eliza’s own great-grandmothers was… Hannah Greenstreet, born in the 1750s. There have been Greenstreets here since at least Chaucer’s time, and an Adam Greenstreete took part in Jack Cade’s rebellion, marching from here back to Blackheath. The green street – my ancestors even shared their name with this ancient road.

A couple of miles along, this amazing site brings the Romans and the medieval travellers together: Stone Chapel, believed to be the only place where a Roman temple directly became a Christian church, and you can still see how the different eras added new chambers on. But for the last 500 years, it has stood a ruin, marooned beside the busy A2.

A medieval survivor a mile more on though is the Maison Dieu at Ospringe, where scholars imagine Chaucer’s pilgrims would have stayed the night before the final push to Canterbury. Royalty certainly stayed here. Seven years after his Agincourt triumph, Henry V was resting here – but this time in a coffin, his final journey into the afterlife, along Watling Street again. And although the building has seen many changes, the heart of it remains, here on the edge of Faversham.

5. Faversham to Canterbury

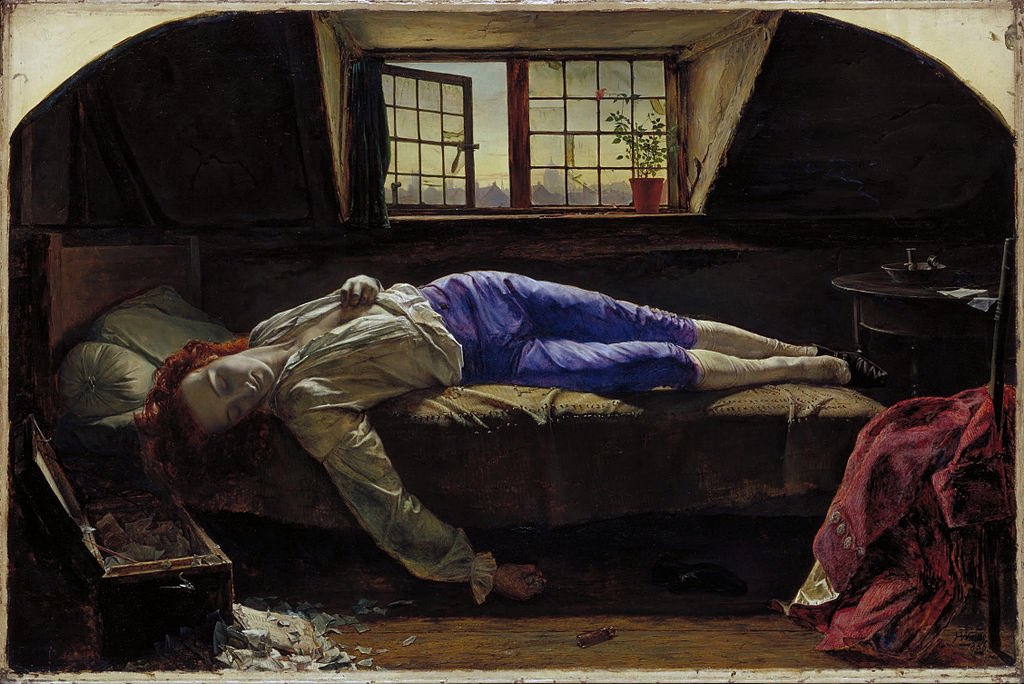

The weary pilgrim pictured here is from Faversham church, in a section which was once the Chapel of St Thomas, although I couldn’t find it due to building work. A medieval painted column is a treasure easily found.

The weary pilgrim pictured here is from Faversham church, in a section which was once the Chapel of St Thomas, although I couldn’t find it due to building work. A medieval painted column is a treasure easily found.

The last place Chaucer actually mentioned was Sittingbourne, but now we have two in a row.

The first is Boughton-under-Blean, perched under what remains of the ancient Forest of Blean – where I used to have to do cross-country runs at school. Now the modern A2 pulls away briefly to leave the village in peace.

On into Dunkirk, where the village sign proudly commemorates the local radio mast – and the ‘Battle of Bossenden Wood’. Another act of rebellion along our street, this was a brief skirmish – some claim it as the last armed uprising in Britain – in 1838, led by ‘Sir William Courtenay’, in fact a chancer called John Tom from Cornwall protesting against the new Poor Laws and who had been locked up in the Kent county asylum.

Victorian scholars argued over the location of the next place Chaucer describes only as a ‘litel toun, which that ycleped is Bobbe-up-and-doun, Under the Blee’, but it seems almost obvious as one bobs up and down the Roman road in this undulating place that it refers to Harbledown. This was certainly important to the pilgrims – Henry II himself made penance for Becket’s death by walking barefoot from here to Canterbury (I was too tired to do that myself).

The Hospital of St Nicholas was founded here in the 11th century, around the same time as the church which survives, which claims to have an old shoe buckle which belonged to Becket himself. There are still almshouses here in an echo of those times, and at last – a well of St Thomas which still exists. In around 1513, the great Dutch theologian Erasmus came here with his English friend John Colet, they were invited to kiss the shoe buckle. Colet angrily responded, ‘Do these fools expect us to kiss the shoe of every good man who ever lived? Why not bring us their spittle or their dung to be kissed?’ The church was locked when I visited, so the shoe buckle eluded me.

Finally, into Canterbury. The original Watling Street turned south-east here and entered the city at the long-gone London Gate, near today’s Rheims Way. In 1379, Simon Sudbury, only two years before his decapitation in London by Wat Tyler and friends, built the Westgate, and what was called the Pilgrim’s Road is now what we call London Road. Here are two hostelries for pilgrims of different kinds. One is the St Eastbridge Hospital of Thomas the Martyr, founded in the 12th century and still an almshouse offering accommodation for elderly people of the city.

The other is a bed and breakfast in London Road, the Pilgrims’ Road – and it’s the house where I lived when I was 15 years old. It’s where I stayed at the end of this walk. Did it feel like home? I’m still thinking about that.

Conclusion

Where we are ‘from’ is complicated. A DNA test proved my Kentish heritage but also shows my genetic lineage is 4% from France – no surprise, as I have a French middle surname which I now know some of the history of and which may go back to Huguenot times (many of those original refugees of course settled in Canterbury and in Rochester). And 15% of it seems to be from Sweden and Denmark.

Which brings me to the Jutes. Archaeologists refer to the ‘problem of the Jutes’ – we don’t know much about them other than that they settled in both Kent and around the Isle of Wight. How distinct they were from the Angles and the Saxons isn’t very clear, and over there in Jutland, there seems little evidence of them. In Kent, the ‘ing’ place names – like Sittingbourne, Newington, Ospringe along our Caising Street – may be Jutish. Is my Kentish DNA pointing back further in time to Scandinavia? Is that where I’m from? But we’re all fossil records of ancient migrations.

All along this route I have found vestiges of the ancient ways, echoes and ghosts – of the medieval pilgrims almost a thousand years before us, and of the Romans a thousand years before them. Signs persist, but they mark absences. Perhaps that’s what our identity and sense of belonging is too – a form of cognitive dissonance, holding multiple versions simultaneously. The self is like the ever-changing road, and the journey is our real home.

The weary pilgrim pictured here is from Faversham church, in a section which was once the Chapel of St Thomas, although I couldn’t find it due to building work. A medieval painted column is a treasure easily found.

The weary pilgrim pictured here is from Faversham church, in a section which was once the Chapel of St Thomas, although I couldn’t find it due to building work. A medieval painted column is a treasure easily found.