Today I’m embarking on another London walking expedition… Join me on a 6-mile walk as I listen to the echoes of a Saxon-era cult, and learn about some literary legends, lost spas… and a walrus. I give you: #pancrasday

Today, 12 May, is the feast of Saint Pancras, a little-known saint whose name is writ large in London, and commemorated in various UK churches. He was a 3rd century Turkish-born Roman who converted to Christianity & was beheaded c.304AD, perhaps by emperor Diocletian. #pancrasday

Pancras/Pancratius (whose name means holder-of-everything) was venerated by the 5th century (he’s patron of children). Allegedly his head remains to this day in Rome’s basilica of San Pancrazio. But how come he’s all over (mostly southern) Britain? #pancrasday

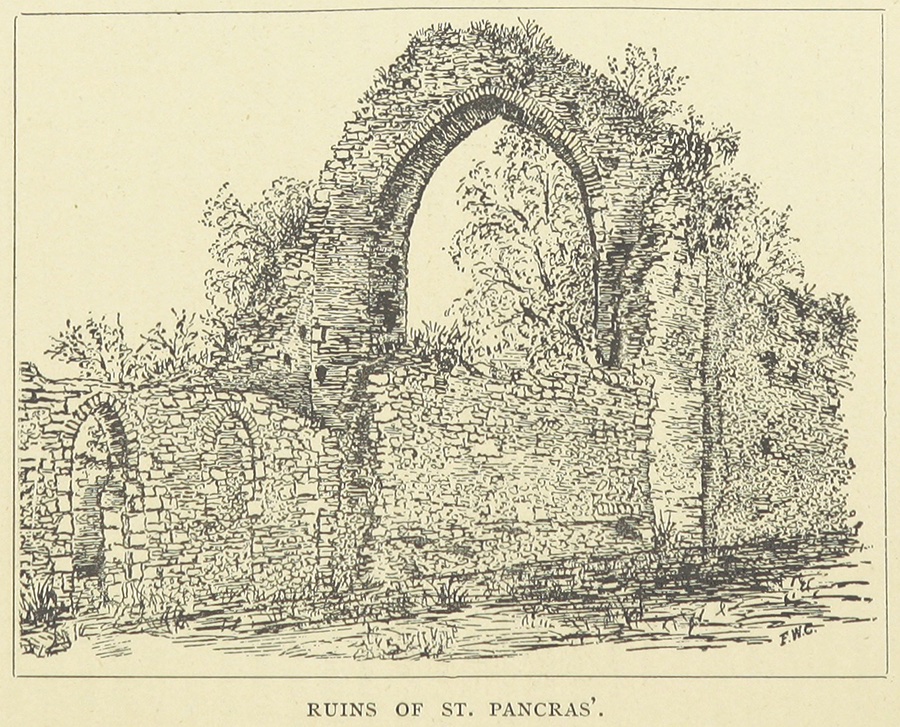

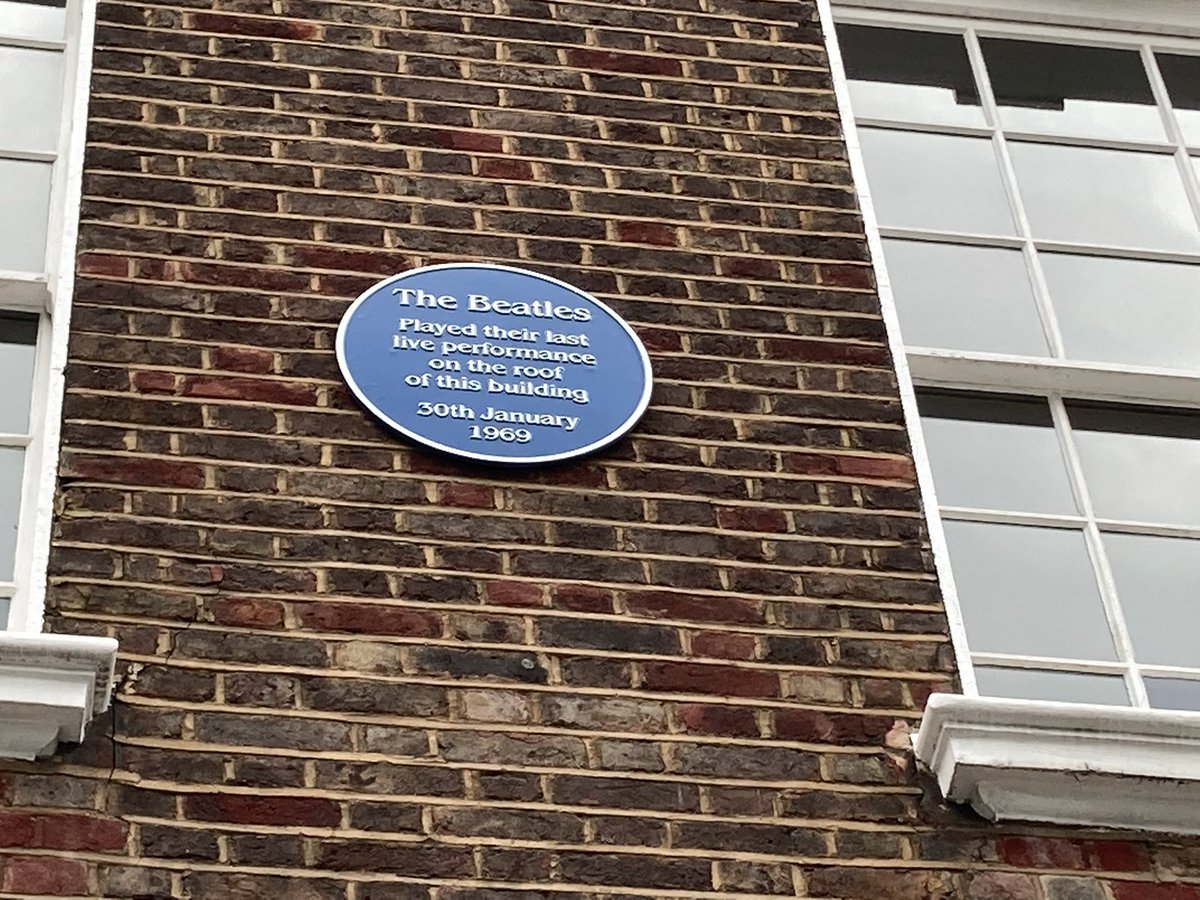

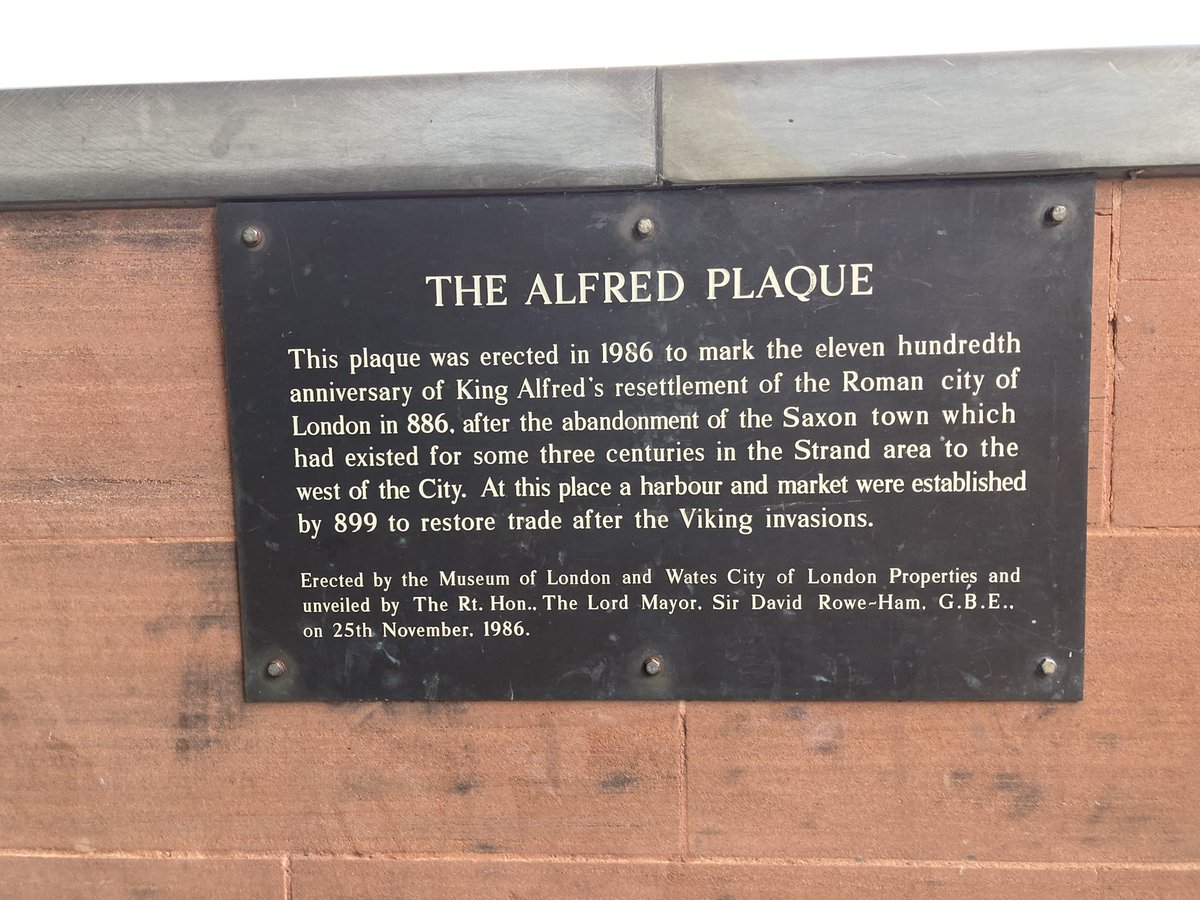

The answer lies with St Augustine, the chap who came to Canterbury in 597AD & brought relics of Pancras with him (history does not record which bits) & the associated cult. Augustine’s 1st church in Canterbury (see pic of surviving ruins) was dedicated to Pancras #pancrasday

Plus a story tells that the monastery in Rome where Augustine had been prior was built on land once owned by Pancras’s family. Bede wrote of the relics in Northumbria c.60 years after Augustine came – Pancras became important here. Join me at 11am! #pancrasday

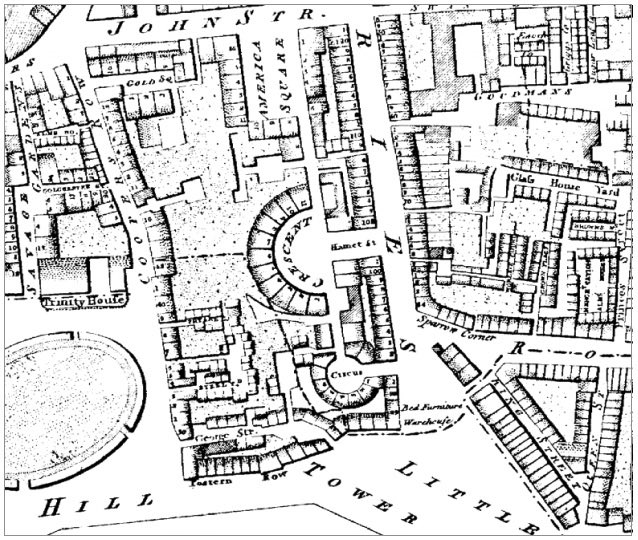

My London #pancrasday route begins of course at St Pancras station – more on that shortly. Along the W side lies Midland Road, built with the station, to the east of Somers Town. The railway development caused this to become a slum. (Map via http://theundergroundmap.com) #pancrasday

The district of St Pancras began as a parish but eventually encompassed dozens of parishes as the population rocketed in the 19th century (now in Camden borough). Swift’s Tale of a Tub is set in Pankridge, a version of the name Pancredge used since the 17th C. #pancrasday

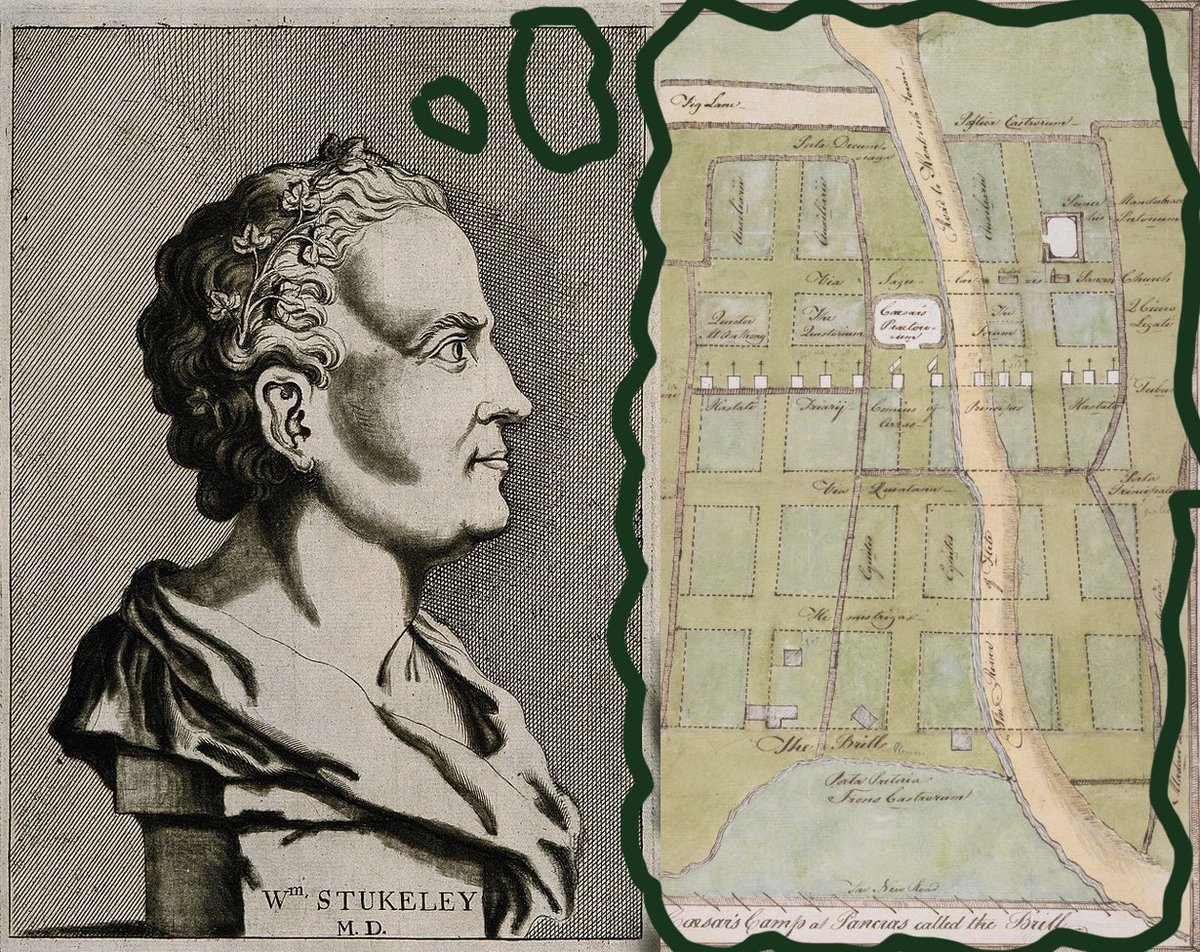

Midland Road passes Brill Place, named for ‘The Brill’, earthworks which in 1750 William Stukeley fancifully imagined was where Caesar had held camp. But there were civil war defences here at Brill Farm in 1642 – and in fact a Roman road passes across here too. #pancrasday

Just W of here was a 15-sided building called The Polygon (demolished 1890), where writer William Godwin and feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft lived – she died in 1797 giving birth to their daughter: later Mary Shelley. Dickens lived here when he was a teenager. #pancrasday

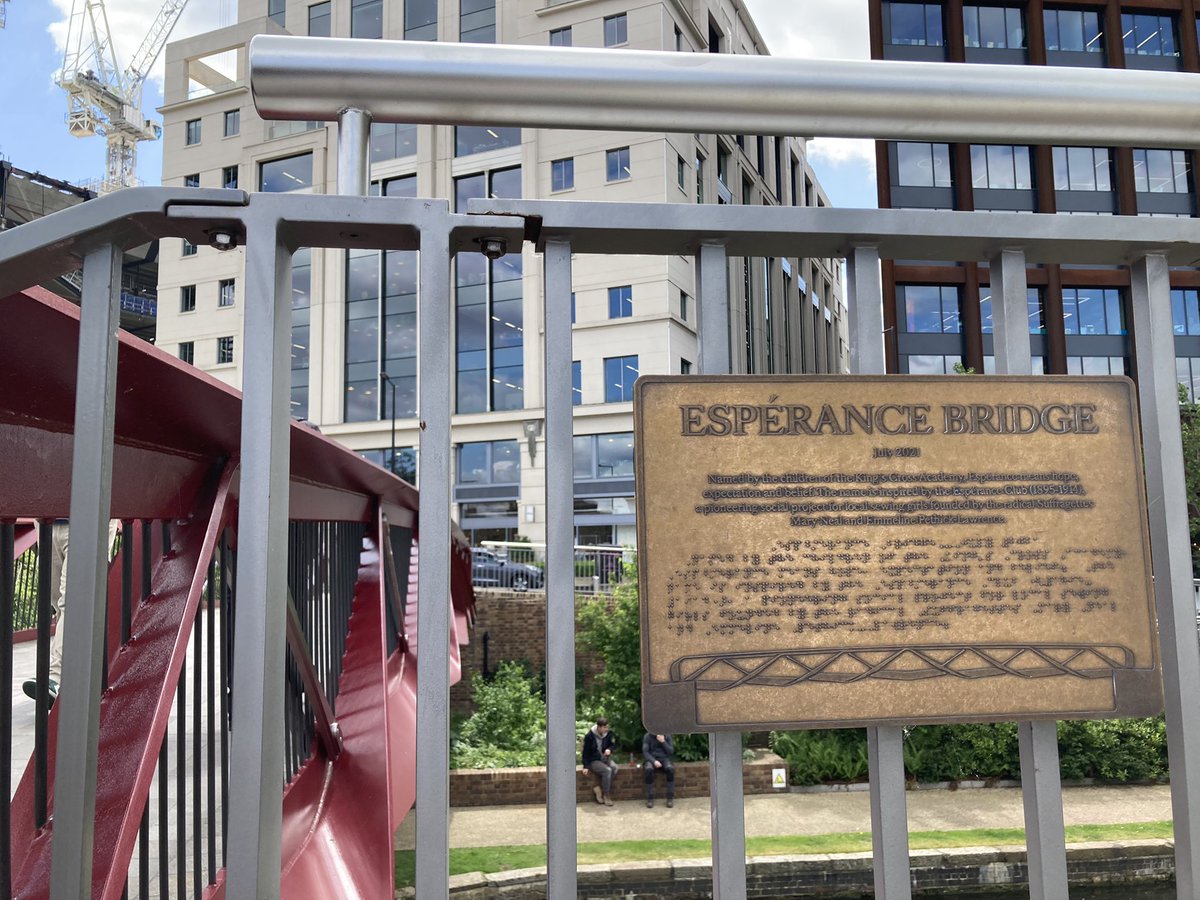

Here’s hope. #pancrasday

Here’s amazing St Pancras Old Church, packed with history I can only touch on. Some have claimed it as England’s oldest but evidence lacks – that gong goes to St Martin, Canterbury, but St Paul’s in London is 7th C. & St Peter-upon-Cornhill could be even older. #pancrasday

St Pancras is at least Norman, and there could be a Saxon origin even. Documents date from the 11th C. and there’s an ancient altar stone (prob. Norman) found during a Victorian rebuild (1848) – plus some Roman tiles. 50 of Cromwell’s men lodged here and made a mess. #pancrasday

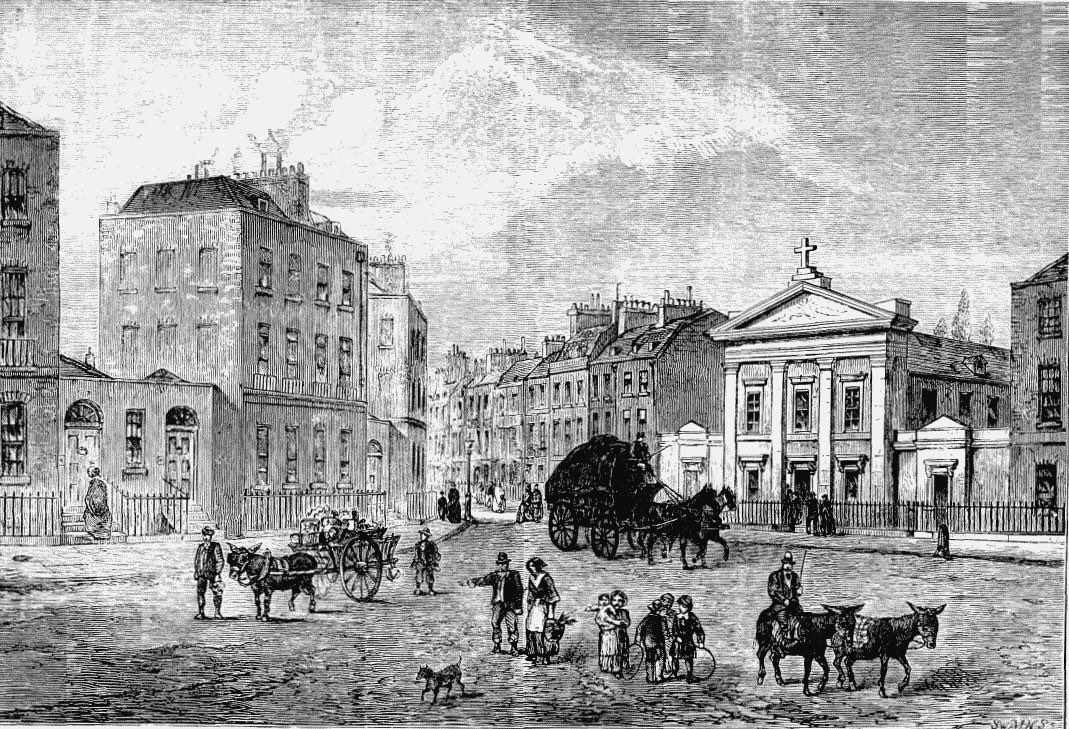

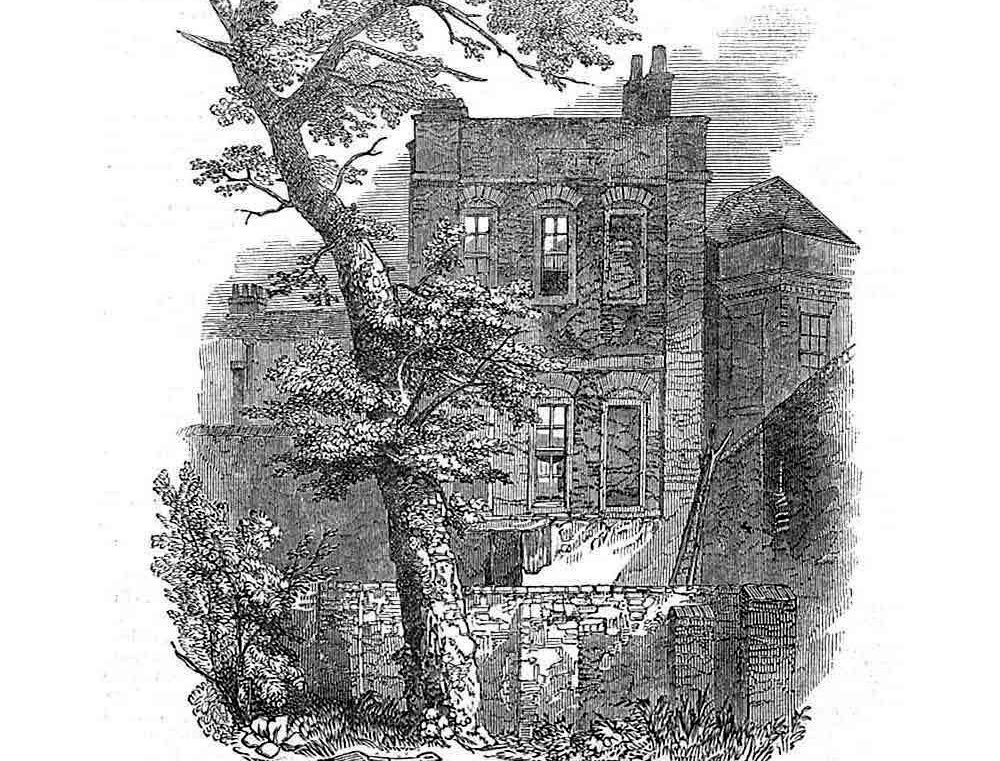

But even by 1593, antiquarian John Norden would write “Pancras Church standeth all alone, as utterly forsaken, old and weather-beaten”. He warned of thieves and said “Walk not there too late”. The church stood beside the now buried River Fleet (pic is from 1815). #pancrasday

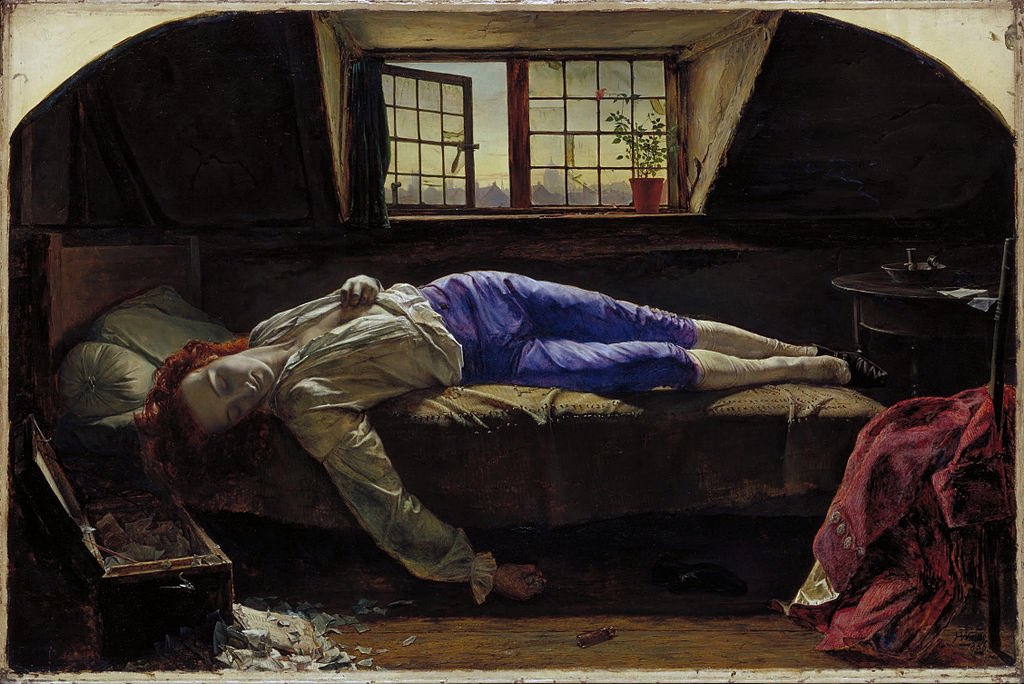

The graveyard has many more stories. Shelley canoodled with Mary here. Dickens fictionalised the bodysnatching. Moody poet Chatterton fell into a fresh grave and killed himself 3 days later. 100,000+ burials were made, including refugees from the French Revolution. #pancrasday

In 1803, an extra graveyard for St Giles-in-the-Fields was added: inmates include John Soane, whose tomb inspired the K2 phone box; Byron’s physician J.W. Polidori, author of ‘The Vampyre’, was another, plus Bach’s youngest son, & transgender spy the Chevalier d’Eon. #pancrasday

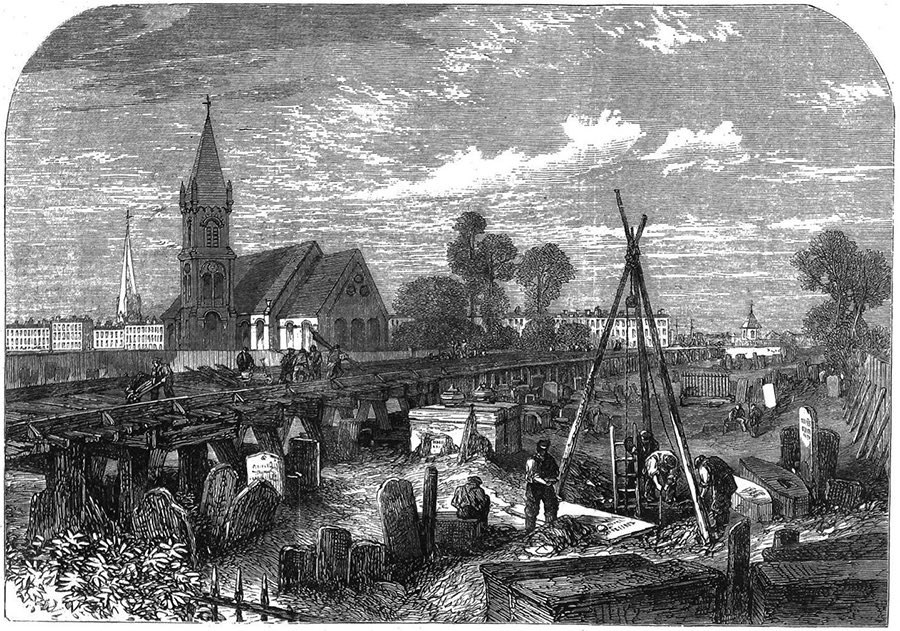

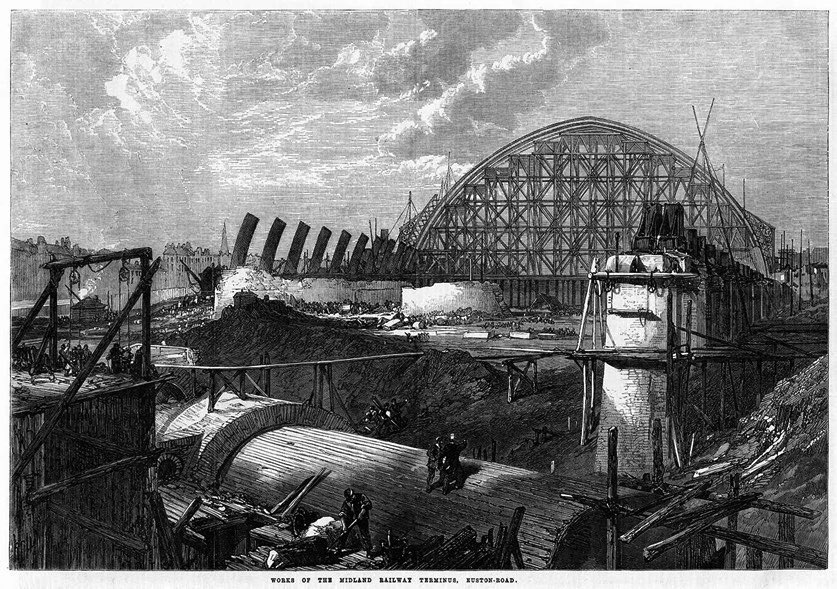

In the 1860s, the Catholic side and much of the St Giles bit was affected by work on the new Midland Railway: many graves had to be moved (an overflow cemetery had already opened up in Finchley in 1854). Contemporaries said it was being “desecrated”. #pancrasday

One workman was trainee architect Thomas Hardy, the novelist. One coffin he found contained 2 skulls. His wife wrote “by the light of flare-lamps, the exhumation went on continuously of the coffins that had been uncovered”. Here’s the Hardy Tree named after him. #pancrasday

St Pancras has long been a lodestone for psychogeographers. If you prefer an alternative take on the Hardy Tree, read this haunting tale by @portalsoflondon: https://portalsoflondon.com/2017/01/20/the-hell-tree-of-st-pancras/#pancrasday

When new work was undertaken for the Eurostar terminal in 2013, a coffin was found containing the bones of eight people… and a walrus! https://www.itv.com/news/london/story/2013-07-23/mystery-of-st-pancras-walrus/ #pancrasday

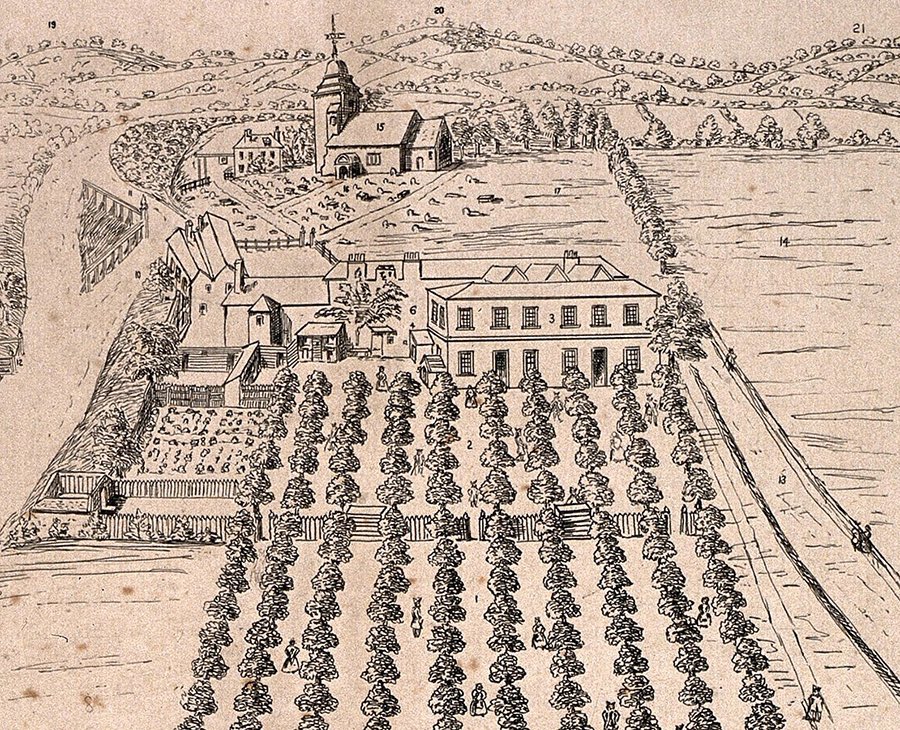

Now forgotten is Pancras Wells, an 18th C. spa (pictured 1730) just S of the church, and the Adam & Eve tea garden nearby, still a tavern in Victorian times. The wells were “surprisingly successful in curing the most obstinate cases of scurvy, king’s evil, leprosy” #pancrasday

Frustratingly there are builders all over the gardens today so I can’t poke around on the side where Pancras Wells was! #pancrasday [update: see below]

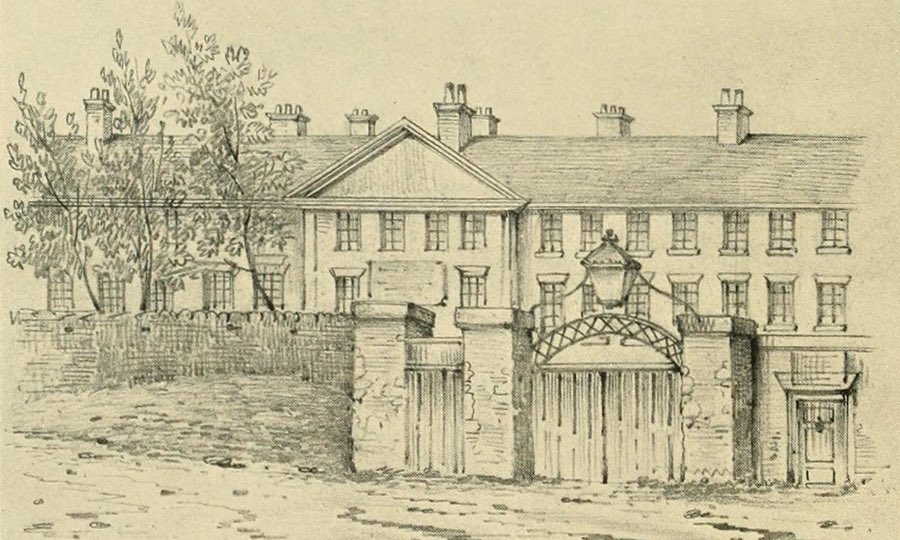

Just N of the church is St Pancras Hospital – previously the 1809 workhouse, later expanded. One inmate was Robert Blincoe, possible inspiration for Oliver Twist. Read my article about him here. #pancrasday

Just N of the hospital is Granary Street, named after a huge 19th C. storehouse for 100,000 barrels of beer from Bass in Burton-on-Trent, later used for storing grain. The 1816 Regent’s Canal runs nearby. #pancrasday

And into Camley Street, home to a wetland nature reserve near the floodplain once called Pancras Wash and on the site of old coal yards. It opened in 1985 and was revamped only last year. #pancrasday

The old gasometers in this area were built in the 1850s. They feature in the 1955 Ealing comedy The Ladykillers. I remember taking rubbish arty pictures of them in the 1990s, before they were decommissioned in 2000; some were rebuilt in 2013 in Gasholder Park. #pancrasday

OK, this is why I’m really here… #pancrasday

Here’s hope again, and on the Pancras children theme. #pancrasday

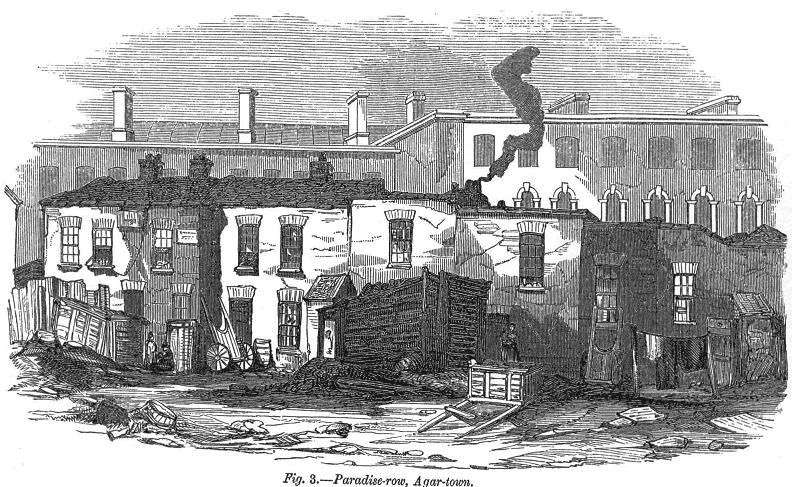

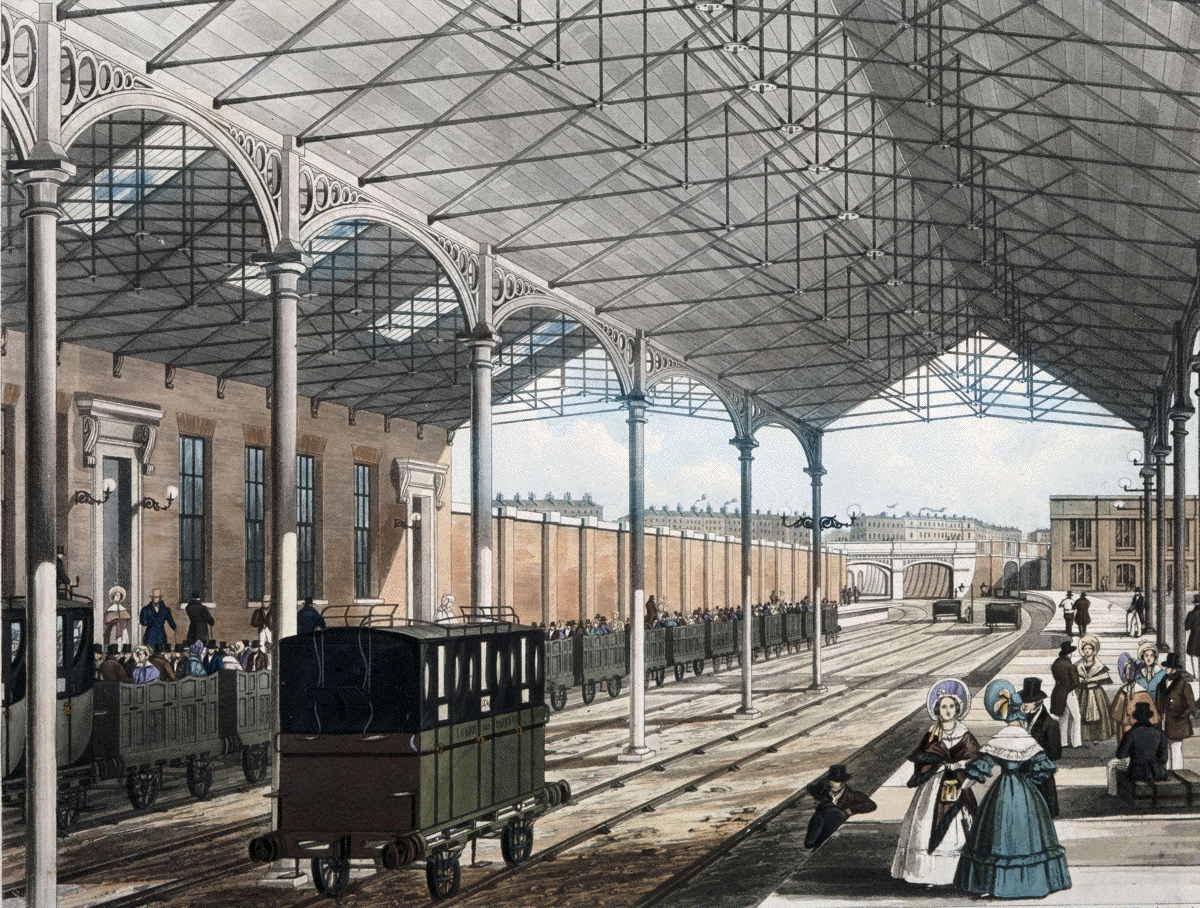

St Pancras station opened in 1868 and the Midland Grand Hotel in 1873. The station site was once Agar Town, a slum named after Councillor William Agar, a Yorkshireman (d.1838) who had a grand villa, Elm Lodge, here. The music hall star Dan Leno was born in the area. #pancrasday

For the next sections of this walk, I’ll be following the route of the River Fleet, which curved past here. Many have written or filmed about it (eg @fugueur) so I’ll only, er, dip in. King’s Cross was once Battle Bridge, allegedly (very) where Boudica tackled the Romans. #pancrasday

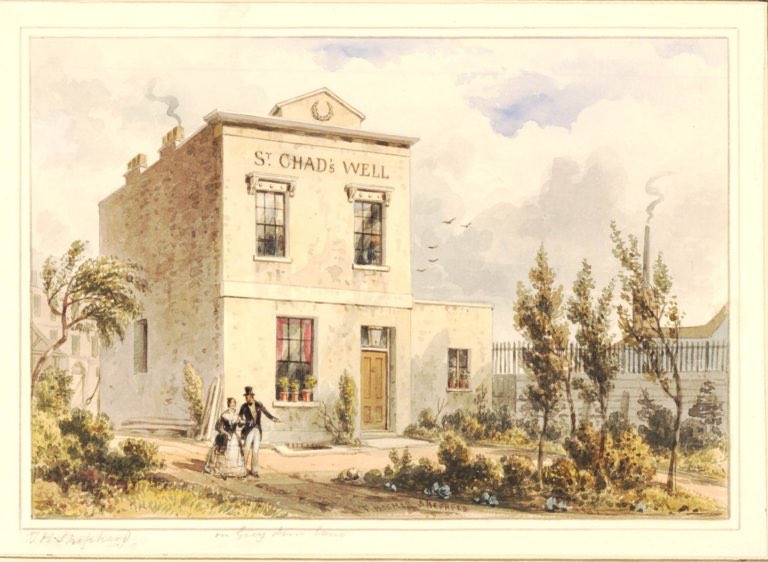

Just off Gray’s Inn Road was once the site of St Chad’s Well, where in 1772 more than 1000 people drank the waters in a week – subscriptions were £1/year. It gradually declined, and the pump room was demolished in 1860 to make way for the Metropolitan Railway. #pancrasday

Another spa site was Bagnigge Wells near King’s Cross Road, then called Black Mary’s Hole. It was favoured by Charles II’s mistress, actress Nell Gwynne. It had a grotto plus bowling green & skittle alley, & 3 bridges over the Fleet. By 1842 it was “almost a ruin”. #pancrasday

As I was passing anyway, of course I stopped at the Postal Museum (@thepostalmuseum http://postalmuseum.org) for a quick trip on the Mail Rail built underground in 1927 for the Mount Pleasant sorting office. Very near the Fleet! #pancrasday

The Fleet also passed the notorious bear garden at Hockley-in-the-Hole, where Ray Street is today. Read my article about it here: https://www.gethistories.com/p/georgian-fight-club-1710 #pancrasday

I can also confirm the rumour you can hear the waters of the Fleet through a grating outside The Coach! 👂#pancrasday

A quick lunch stop at Little Britain feels appropriate, before I’m back directly on the heels of the saint who prompted this. #pancrasday

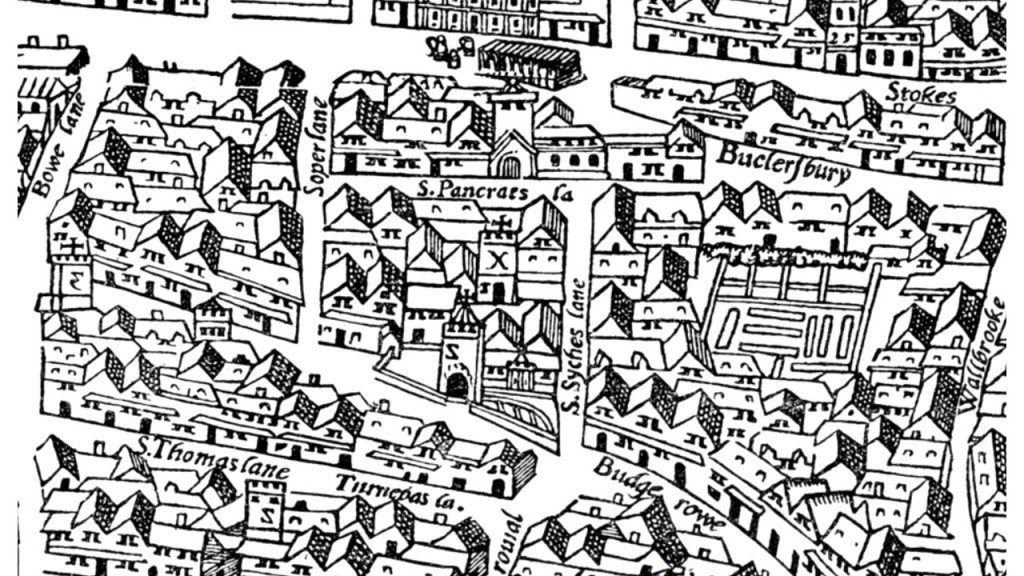

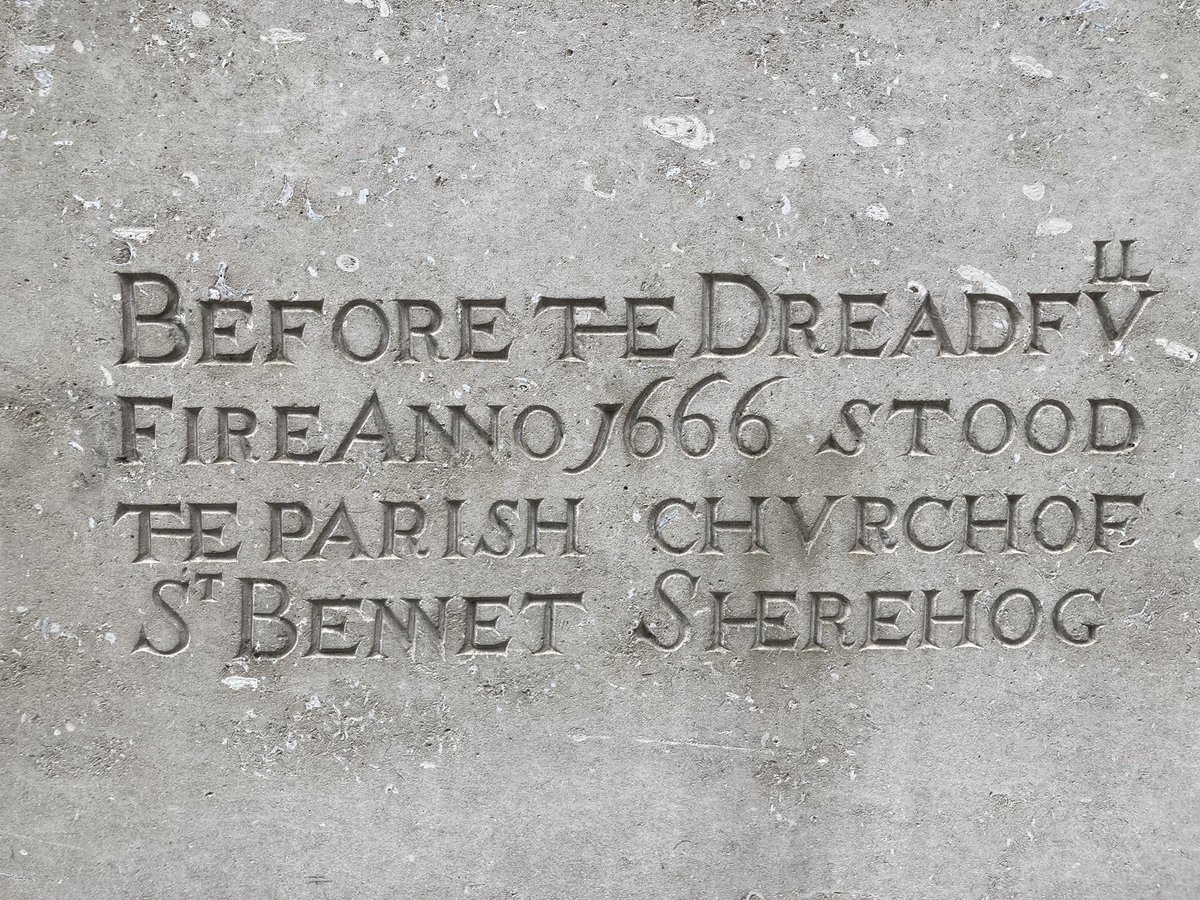

We still have two more London churches named after St Pancras to investigate. Pancras Lane off Queen Street in the City gives a clue to the first. Sadly St Pancras Soper Lane (& its marvellously named neighbour St Benet Sherehog) was destroyed by the 1666 Great Fire. #pancrasday

This St Pancras is mentioned in 13th C. documents and was owned by Canterbury Cathedral; it may have been older still. Some remains are buried beneath 70-80 Cheapside – and this little yard marks part of the burial ground (used until 1853) to this day. #pancrasday

In 1374 the archbishop of Canterbury supported the funding of a bell here confusingly called ‘Le Clok’. In the 17th C. a memorial to Eliz. I and repairs were funded by a Thomas Chapman, who I assume is no relation. In 1598 John Stow called it a “proper small church” #pancrasday

Just E of St Paul’s stands the remains of St Augustine Watling Street, tying together the Roman road and the man who brought Pancras to Britain. This Norman church too was lost to the Great Fire, but rebuilt by Christopher Wren. Most of it was lost again in WW2. #pancrasday

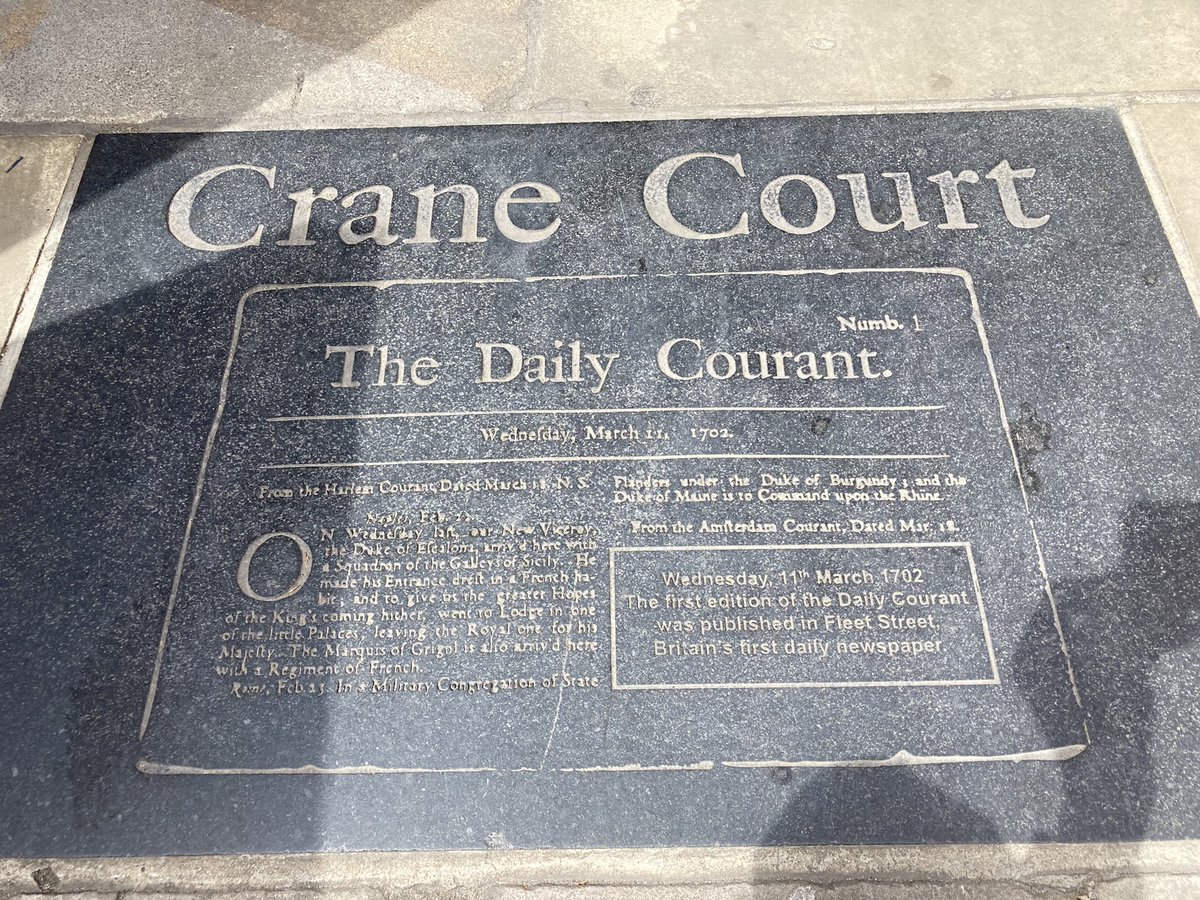

Now I’m heading west along Fleet Street again (see #londonfogg). Here’s Crane Court, where Isaac Newton moved the Royal Society in 1710, and a plaque to Britain’s first newspaper, the Daily Courant. Read my article about that here: https://www.gethistories.com/p/the-first-daily-paper-1702 #pancrasday

At Lincoln’s Inn Fields is the amazing Sir John Soane’s Museum (http://www.soane.org@SoaneMuseum) – as we met him in death at St Pancras, here’s where he dwelt in life. This is the model he made of the same tomb which he kept by his dining table as a memento mori! #pancrasday

Oops – the 6-mile #pancrasday walk has been 9 miles so far…

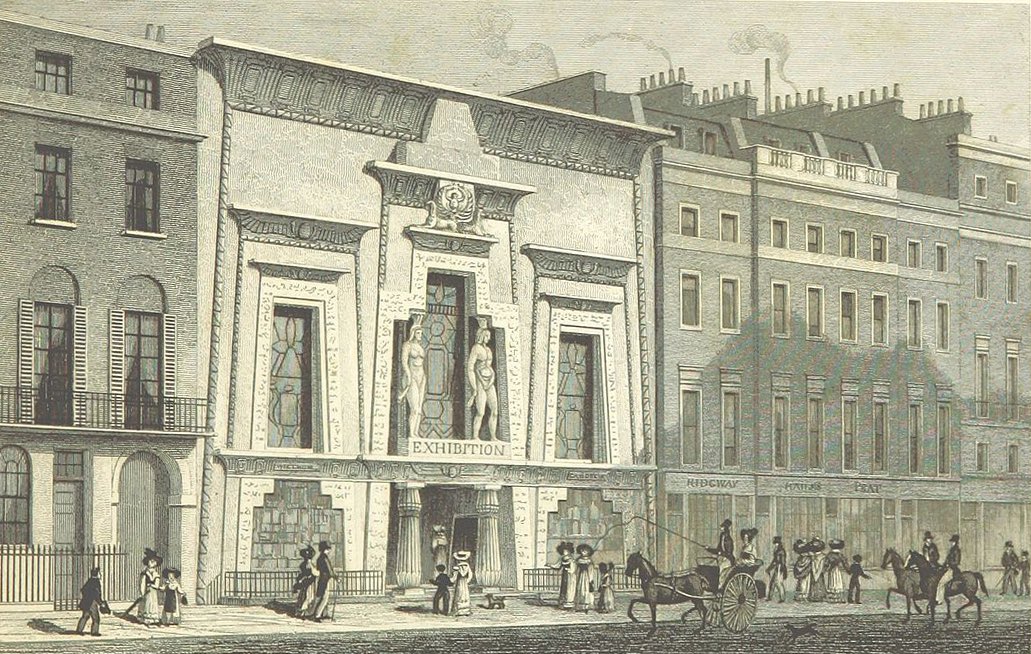

And finally to St Pancras New Church, built 1819-22 as the main place of worship for the old parish – although it is nearer to Euston. It was inspired by a temple and a tower in Athens. It cost £77,000 to build – the most expensive church since St Paul’s was rebuilt. #pancrasday

The church is known for its terracotta caryatids – female figures serving as architectural props – although they were too big when first installed and allegedly had to be, er, pruned. Meanwhile the congregation of the old church protested at this one being built. #pancrasday

(A volatile vestry meeting in Southampton Tea Gardens “was very tumultuous” and a punch was thrown – and at the 1819 stone-laying ceremony “a numerous gang of pickpockets rushed in”. All good fun. #pancrasday)

And on that nefarious note, my #pancrasday walk comes to an end. Thanks for following! (I have plans afoot for historical walks outside London, if you like this sort of thing, and do sign up to my weekly newsletter, https://www.gethistories.com)

Follow-ups

- My article on ‘the real Oliver Twist‘ (a memoir of an inmate at St Pancras workhouse).

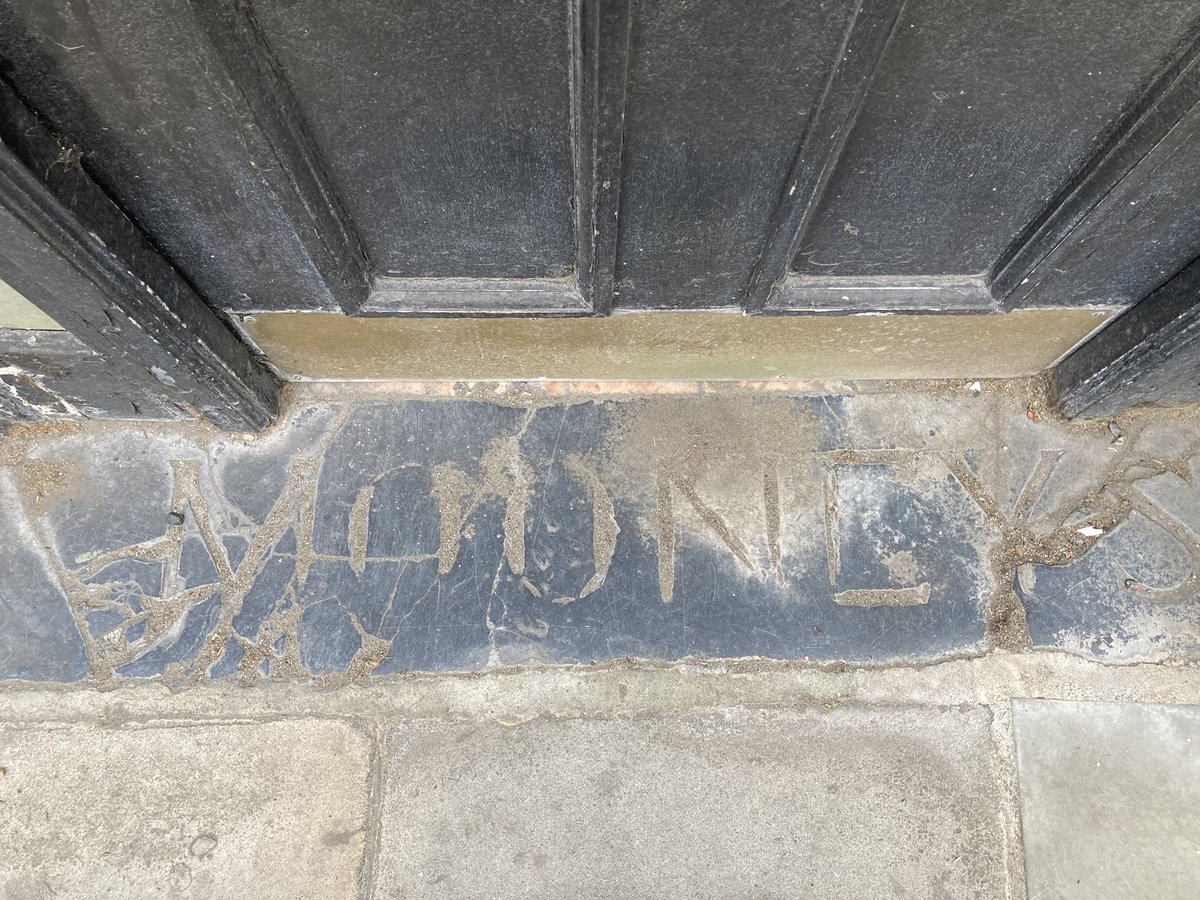

- 3/6/22: On my #pancrasday day adventure a few weeks ago I couldn’t see all of Old St Pancras churchyard due to work going on. I’ve snuck back to visit the corner near where the Pancras Wells resort was, thanks to a sexton letting me through the barriers. Anyone for dominos?